Using People As Subjects

Renting A Mind To Pay The Rent, or Save The World?

When you’re approached in Berlin, you’re unlikely to be asked for money.

If you stand still long enough and watch the mixture of walkers, cyclers, and tram riders fly left to right and right to left, throwing the city’s collective image in tandem, eventually someone will break from the 2D tennis-like back-and-forth of the throng and make their way towards you. Outstretched-hand-first, this someone may inspire in the uninitiated Berlin tourist a reaching toward the wallet - but they would be sadly mistaken to do so. It happened to me outside Berlin Ostbahnhof Station when an Eastern European gentleman approached me and asked for my plastic water bottle.

It’s called the Pfand Bottle Return System: a system aimed at collecting and recycling bottles with monetary rewards for anyone willing to put in the work. Whether the bottle is bought at a bar or a corner shop, it can be returned for a small percentage of your money back if the bottle has a certain sign on it. As not everyone goes to the effort to collect their deposit, they’ll often pass these bottles on to those that do: mainly the homeless. Consequently, around the Berlin streets, you’ll see homeless men and women carrying their lives on their backs along with shopping bags’ worth of bottles for extra change. People are often reluctant to part with their money, but their rubbish? not so much.

I was aware of the Pfand System whilst in Berlin last September, but had not acclimated enough in my short stay to assume the Eastern European man approaching me wouldn’t ask for money. Eyes aimed at my bottle and finger pointing down, he requested it in broken English (I must’ve looked like a tourist as no German was attempted). I passed the bottle on, and he began showing me the signs on the bottles that indicate they can be returned for euros. He then began to tell me about his life.

I’d love to tell you I remembered everything he told me, but I simply can’t. A heavy accent further blurred by a language barrier made keeping up with this man’s story a challenge – one that I ultimately failed. Despite this, I remember fragments: mother in Ukraine; travelled West looking for work; he had a kid (maybe two?); cautioned me against ever accepting a drink from a stranger (according to him, opportunists will offer tourists a drink containing a cocktail of drugs so strong it would knock them out cold); and that his main source of income was through begging and the PFand Bottle Return System. I liked him - that is partly why he has become my introduction; there are also other motives at play here.

When writing, you need stories and subjects. Both can either come to you, or you to them; in this case, I experienced the former, and it has benefitted me immensely (introductions are hard to do!). What to the man was a brief encounter with a random Englishman has now been imprinted in the remote corner of Substack known as Behind The Selador, FOREVER, and all because I needed a way to introduce this week’s topic: using people as subjects for your writing and how to do so in a slime-less way.

There is a level of manipulation inherent in wanting to make people into subjects for your work. Whether they’re aware of it or not, a person can become a source for your creative endeavour. I had not necessarily gone to Berlin with any creative aspirations in mind, but when approached by the unnamed Eastern European man, I couldn’t help thinking he had some stories to tell that might be useful. A faulty memory and a language barrier made sure this would not be the case (arguably, as I’m evidently getting my money’s worth right now). The above-storied fragments of understanding gave insight into personal tragedies, some of which bordered on hilarious (at least judging by his opinion and certainly not my own). Now those stories are all gone and likely laid out on many others’ consciences. But wherever he is and whoever he has spoken to next, I hope, of all the consciences to fall on, my brief Ostbahnhof Station companion’s stories could reach just one person - a person I believe could do them justice.

Recently, I have been obsessed with the writer William T Vollmann. Vollmann, unlike many writers today, lives the subjects he writes about and grants them the respect all writers/journalists should. Here is a short list of a few things he has done for his work:

In the 1980s, he travelled to Afghanistan to support the Mujahideen against the invasion of Russian forces;

he covered the Bosnian War in the 1990s;

he travelled around the world asking people, “Why are you poor?” to try to understand why some people have some and others don’t in the early 2000s;

He train-hopped around America in the late 2000s;

dressed up in drag and walked the streets at night in the 2010s;

and, as recently as 2025, he was in Ukraine writing his pieces Drones and Decolonisation for Granta Magazine 1

Needless to say, Vollmann has travelled a lot and absorbed more than his fair share of stories. His subjects often fall under those who are oppressed by something. But whereas some attempts at journalistically shining a light on injustice seem self-serving or more focused on careerism than humanitarian concerns, with Vollmann, it does not. Maybe I’m reading him wrong, but when you look into his work and his interviews, Vollmann appears to be someone deeply impacted by the thought of anyone having below the required amount. His essay Four Men (Published in Harper’s Magazine in November 2023) best displays the internal conflict of his journalism and the morals behind using people as subjects.

Four Men: or, How To Rent A Mind

“[...] I set out to rent the mind of another doorway-inmate” - Four Men by William T Vollmann.

Four Men features in the November 2023 issue of Harper Magazine and was a revival of Vollmann’s output. Having spent his career prolifically writing in a wide range of genres, he took a break following a run of bad luck between 2020 – 2022; a run that included a cancer diagnosis, being hit by a car, being dropped from his publisher after thirty years of working together, and the death of his daughter Lisa Vollmann. Not necessarily in that order, it is understandable that such a tragic streak would slow you down – even if you’re William T Vollmann.

But he came back, picking right up where he left off. Four Men is an essay that focuses on three homeless men, with the fourth man being Vollmann himself. In typical Vollmann fashion, he wants to write about those most afflicted by the incoming storm in Reno, Nevada, and to do so, he set out into the cold night in search of anyone willing to talk. Vollmann aimed to answer the basic question “Why do I [Vollmann] get to sleep inside when you [the homeless] don’t?” Where this essay differs from previous work, however, is the moral quandary at stake when using people as subjects.

Four Men is a self-conscious essay. Not in the Gonzo sense – although it is to a degree Gonzo – but in the transactional. Vollmann knows there is a moral grey area to what he is doing. Categorising himself as among those on the “inside” and the three men on the “outside”, he seeks both to represent the latter whilst remaining away from their predicament via this essay. For every subject or story found in the cold streets of Reno that March, Vollmann can monetise. In tongue-and-cheek fashion he makes mention of a death on the street making a good story for his essay, or another meeting with one of the three men adding a few extra words (and thus a little more money) to Four Men, or that his search for three other men as being indicative of keeping his essay title, or that his desire not to be an outside man has led to him needing the outside men for raw material so he can write and get paid, thus remaining, an inside man:

“Although any true-blue patriot would assume that Washoe County so brilliantly plans and builds as to maintain on offer exactly as many beds as each storm, layoff, eviction, or foreclosure demands, I in my perversion began wondering again. Specifically, I wondered whether somebody might die of exposure tonight. Surely not right at Safe Camp—for that place sounded so safe!—and preferably not as a result of getting turned away from Safe Camp, which might reflect unhappily on Washoe County. Most likely nobody at all would die on Reno’s streets between now and tomorrow morning, so why fret? Of course, a corpse on the sidewalk would increase the value of this essay.” - Four Men by William T Vollmann.

It’s a confusing moral quandary: is it right to get paid to use other people for their suffering? Annoying answer: It depends. I’ll answer later in full, but first, let’s take a quick look at the three men themselves.

To respect their privacy, Vollmann didn’t give the men’s real names. The first man is called Roland. Coming across Roland minutes after leaving his apartment, Vollmann invited Roland for a beer in the Club Cal Neva casino. Roland obliged. The two got talking, and their worries for the impending storm clashed: Volkmann’s was concern over Roland’s plans, Roland’s were a general apathy towards anything (Vollmann notes how Americans often blame their homeless on themselves as opposed to in other countries where the homeless will blame their government). Roland’s answers to Vollmann’s questions were all practical and without much description: If it rained, Roland would sleep inside; if he got lonely, Roland would find people to talk to; if he was told to get lost, Roland would get lost.

Vollmann tries to find comfort for himself in these answers and Roland’s general attitude. If Roland was fine, why couldn’t Vollmann be fine with Roland’s situation? It’s an understandable question to ask oneself when face-to-face with a living, breathing human being who is forced to bear conditions you couldn’t bear yourself. Vollmann internally justifies it as such:

“In brief, he seemed neither worried nor happy about impending difficulties. Maybe his passionless affect obscured some other feeling, but I would rather believe (wouldn’t you?) that this man was at ease—in which case I need never invite him to spend the night in my warm rented room. Come to think of it, I already possessed an exemption from such duties. For God, chance, or economics had long since fixed our divergent destinies: He was an outdoor man and I an indoor one, so that whatever happened on the sleety side of my picture window could be left to Mother Nature. Oh, yes, he seemed to be doing well enough.” - Four Men by William T Vollmann.

The two parted ways affably, Roland returning to the streets and Vollmann to his apartment.

The second man was Jesse. A tall and stern-looking man who was, by Volkmann’s account, a little more dislikable than Roland. Once again, Vollmann offered a drink, and the two got talking. Homeless since 2008, Jesse had come to Reno for a change of scenery (having previously been in Knoxville). When speaking to Vollmann, he happily gave up his past but looked at Vollmann with an expectation. Vollmann understood this look to mean an additional gift besides the free beer and promise of twenty dollars that Vollmann had offered. Eventually, he came out and asked, “Can you buy me a blanket?” Vollmann (who does not drive due to impaired eyesight) said he could not, as the closest place was hours away. Jesse gave a look of disappointment. After their talk, Vollmann left Jesse feeling guilty, knowing he had left him blanketless to the elements.

The last man Vollmann named Happily. Happily was monk-like in his serenity and stoicism. As the last two men seemed (understandably) downtrodden by their lives on the streets, Happily looked exactly as his fictional name would suggest: happy. Happily is the symbol of remorselessness. As Vollmann admits his negative feelings towards Jesse (due to guilt and his innate indoor-man revulsion toward begging or conning from the outdoor man), he notes his affection for Happily as he sits in the cold wind without concern. His look of concern (or lack thereof) not only impresses Vollmann due to his resilience, but it also absolves him too. As he does many times in the article, Vollmann looks for signs of happiness in the three men, not to feel good for them, but to feel good about himself. Vollmann knows, no matter how much he cares about the outdoor men, he would do anything to remain on his side of the apartment window.

And that’s the main conflict permeating the essay: whether covering these men is helping them or using them. Many times throughout the article, Vollmann self-deprecates his role as a journalist as he uses these three men to further his piece. In using these men, he is slightly improving his bank account, which had dwindled within the last few years due to inactivity. To Vollmann, his intentions are pure (he offers money, a place for them to be warm for a few hours, and does not incentivise anything beyond the interview itself), yet he still understands his number-one concern is getting paid:

“Taking in all that had been a full day’s work, at least for an aging indoor man, so I returned to my room to get warm. I felt drowsy. Come to think of it, I had been tired all year. Maybe my third man would be so well-spoken as to improve this essay into a prose poem, although what I actually wanted to improve was my bank balance—for I was slipping, you see. Everything wore me out. By then it was four in the afternoon. I sat looking out my window at the juniper trees, which lowered their heads, shook their necks, snorted, and trembled in the wind as if eager to become horses and gallop off to some dark ending.” - Four Men by William T Vollmann.

What also hangs over the article is a personal tragedy in Vollmann’s life: the loss of his daughter. This loss caused the aforementioned break in Vollmann’s output. Four Men, thus, was a return to work of sorts, yet the essay provides a wider personal perspective concerning Vollmann’s legacy and his end goal when covering subjects:

“Had I been where she imagined or hoped I was, I would have rushed to hide the alcohol, as usual, then fed her, wrapped her in blankets on my sofa (being also bulimic she was thin and got cold easily), and stayed beside her, postponing for another day my brilliant monetizations of the miseries of others. (Oh, I was plenty compassionate, all right; I had written books to prove it.)” - Four Men by William T Vollmann.

The death of Vollmann’s daughter increased the critique of self Vollmann displays in his essay. His guilt paralysed him, and he began to doubt his own ability to be compassionate towards others. This self-critical tone in Four Men is best captured when Vollmann describes himself as “renting a mind”. The phrase shows the transactional arrangement between himself and all the idiosyncrasies that culminate into what we call a “person”, when he asks these people to express themselves for his raw material. Vollmann has been doing this for years, but losing his daughter evidently made him consider his own death, and naturally, what he has done with his life.

In Four Men, Vollmann would have you convinced he has done nothing.

Who’s Helping Who?

But that is not the case. Vollmann, whilst at times naive in his idealism, has done more than his fair share for his subjects.

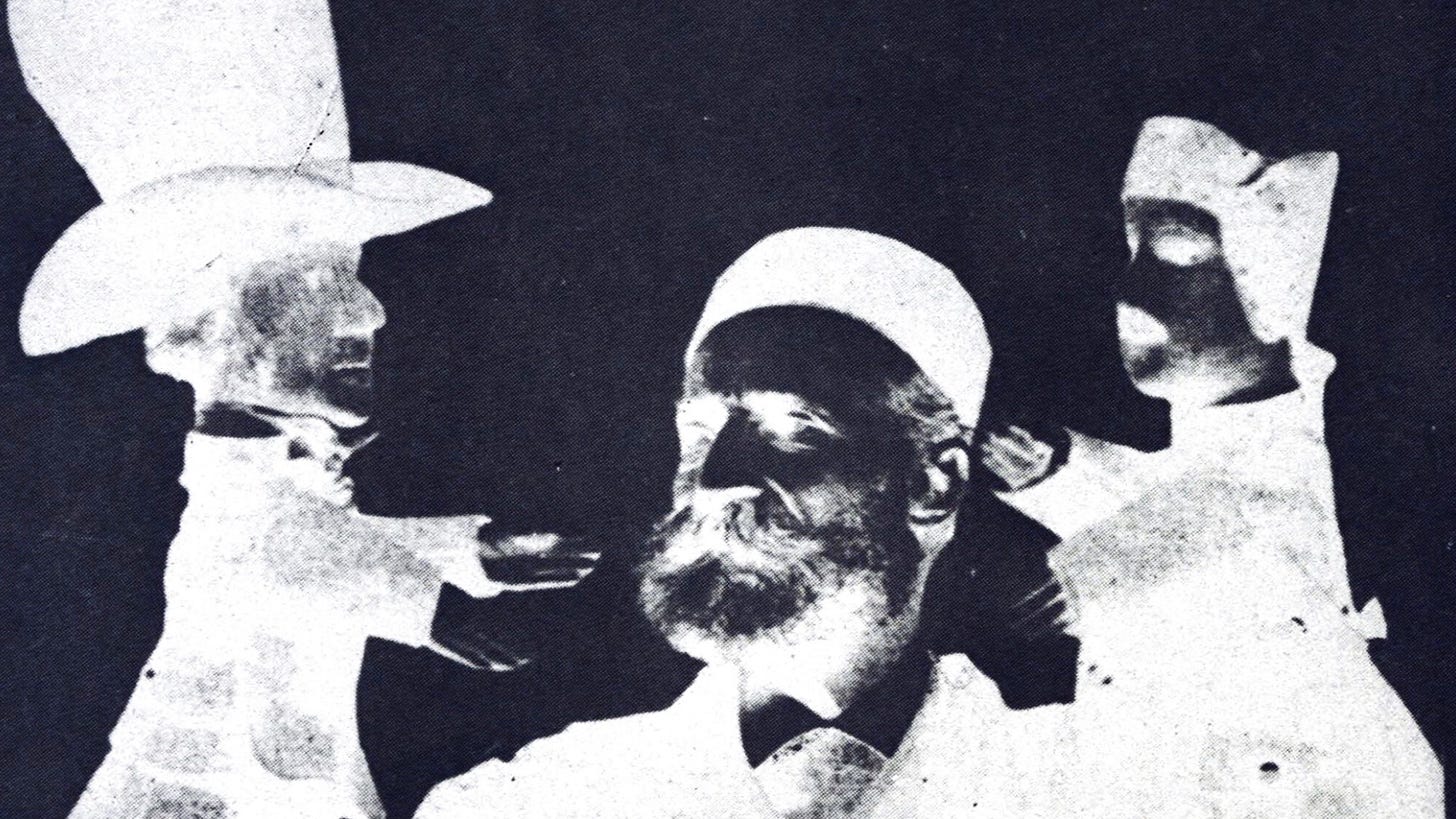

Dating back to his beginnings as a journalist/writer, Vollmann has always injected himself into the environments of his subjects. As previously touched upon, in the 1980s (when Vollmann was 22 years old), Vollmann travelled to Afghanistan to “help” the Mujahideen. Vollmann had read about Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan and was so disgusted with what he read that he dropped everything to try and make a difference. Whether an egotism took over (who thinks they would be of any help in that scenario?) or a conscience so strong he couldnt not help, Vollmann nevertheless put himself in the way of danger for little to no personal gain. His only reward: material to write about.

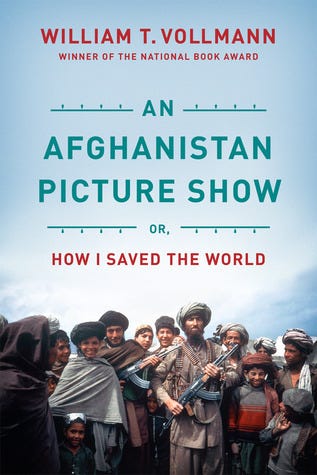

His writings from that time would be comically told in his book An Afghanistan Picture Show: Or, How I Saved The World, published in 1992. The title, whilst containing the jovial self-deprecation of a Vollmann who was looking back at this episode of his life a decade after it happened, further complements the struggle all well-meaning writers, documentarians, musicians, or artists face when attempting to help: their confrontation with an ego that suggests that they are the ones to help in the first place.

When speaking of An Afghanistan Picture Show years following its publication, Vollmann makes the humble statement that he had travelled to Afghanistan to help, but the Mujahideen had instead helped him. Not only did they literally help him (Vollmann was suffering from dysentery and could have been left for dead should they so have wanted to do so) he had also been helped in his personal career goals. He got himself published and eventually turned his experiences into a book, which – whilst not making loads of money – certainly brought in an income.

I am not criticising this. Vollmann’s actions as a naive 22-year-old were 100 steps above the naive actions of a 22-year-old reposting a political meme on social media. At least he went and placed himself in harm’s way with good intentions. But it was naive nonetheless.

I think there is an egotism to believing you’re the one who can help. If helping makes us feel good about ourselves, then who are we helping? Evidently I am not talking about pulling someone out of a burning car wreck; I am speaking of decisions like Vollmann’s to travel to Afghanistan, where he became more of a burden than a helping hand. It’s reminiscent of the character Pyle in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American: the over-idealistic westerner who thinks he has all the answers, only to make things much much worse. Good intentions can prove detrimental.

But this is not the first time Vollmann has been naive. In fact, his naivety follows him. When I say this, I don’t mean to throw shade; I am merely saying that to approach everyone with the expectations of good intentions being reciprocated (particularly when that person is down-and-out and will do almost anything for money) guarantees a few burns along the way. Yet, Vollmann understands this (is he really naive then?) and holds no grudges, as, I imagine, his intentions are not always so pure himself; at the end of the day, Vollmann needs stories and subjects. Vollmann makes mention of this in Four Men:

“Once upon a time, in Bangkok, having paid and photographed an armless man for a book of mine, at the close of business I happened by him on a pedestrian overpass, right when he was unbinding his arms from behind his back. I felt neither betrayed nor sorry for him but mildly admiring of his acumen. And that beggar woman in Mexicali who at my approach would always pinch her baby to make it scream, then put on a woeful look while holding out her paper cup—well, in her case I occupied myself in deciding whether to reward her cruelty with a few pesos or ignore their misery (I paid, of course; I generally do), all the while pitying them, even the baby, only as members of a general class, because so many other desperate, patient, sad, or threatening people vied for my pesos!” - Four Men by William T Vollmann.

And so it can be hard to tell who is helping who sometimes. It seems as if we assume the person helping is the one with the biggest bank account, but - as shown above with Vollmann and the Muhajideen - this is certainly not the case. Throwing yourself in harm’s way does alleviate the manipulative feel of using people as subjects, and so I believe it can absolve guilty feelings - so long as it does not fall into voyeurism.

War Correspondent Sebastian Junger commented on the potential for voyeurism in war reporting, as the journalist – despite being there in the flesh – is one step removed from the subject. In other words, and particularly in the case of war journalism, the journalist can always go home. The same applied to Vollmann. When he went out in search of his three men, he always showed the one-step removal via descriptions of him staying in his rented apartment, lying in bed with the heating on.

In entering into the world of the subject, the journalist has agency. The journalist chose to be there. Therefore, they are immediately better off than their subject (if covering a subject involving conflict, poverty, oppression, etc.). In an interview uploaded onto the LA Review of Books’ YouTube channel in 2014, Vollmann expanded on his thoughts on witnessing violent death:

“Compared to a soldier I’m very very lucky. One of the reasons that witnessing violent death is so awful is because you see people’s agency taken away from them. And then you tend to feel more powerless yourself. But if you’re a journalist and you’re going in and out of war zones then you’re insulated to some extent and you can always think, ‘Well, I signed up for this.’” - William T Vollman.

He then explains a time when agency became a comforting thought. In 1994, Vollmann was one of three men inside a vehicle that was ambushed while covering the Bosnian War. Whilst driving through Mostar – a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina – their car ran over a landmine. Vollmann was sleeping in the back of the car when the mine exploded. From his own recollection, he remembers the smashing of the windscreen, shots, his friend’s scream, and nothing else. Thirty years later, in the aforementioned interview, Vollmann says his primary source of peace in the incident can be found in his two friends’ agency. They had both wanted to go there, and for that, they unfortunately paid the price - but at least they had a choice.

“When my two friends were killed in Bosnia of course I felt very very upset. And at the same time I didn’t have to feel as upset probably as I would have if we’d all been from there. If we were just friends in the neighbourhood and they’d been killed, and we had no choice in the matter. So I think reminding ourselves of our agency in life is a way to fight off some of the damage.” William T Vollman.

I guess Vollmann’s main goal when covering these subjects is respecting the lack of agency given to those afflicted with poverty, war, or oppression by using the privilege of his own agency to highlight the lives of those without. It can be easy to self-deprecate (as Vollmann does in Four Men) when a monetary benefit is involved, but I don’t believe the help is all one-sided. Vollmann’s three men did not entirely help him and nor did he; they both work symbiotically to make their situations a little better. Vollmann got his subjects, and the three men were paid for their time.

And so, to the question “who is helping who?” I say, if done correctly, both. Vollmann’s work, if only a little, will raise awareness. But even more importantly than that, I think his commitment to his morals and values will have a far wider-reaching impact. His work isn’t particularly popular right now, but in time, he will be appreciated (hopefully he’ll be around to see it happen). Despite his personal tragedies, Vollmann still decided to write a comeback essay about others. He could’ve only written about himself - but that isn’t Vollmann’s style.

I don’t believe Vollmann is going to single-handedly solve anything, I just think his example will spread enough so that by the time of his death (hopefully many years from now), more people would take a hands-on and initiative-driven approach to issues in the world, even if done so naively, than they did when he was born. You can’t live in black and white, but you can do the best with what you have. I believe Vollmann has, and continues to do, exactly that.

The Best He Can

All examples (bar his work in Bosnia and Ukraine) in this list show up in books I will name later in the article. If you want them bunched up neatly, here they are in chronological order: An Afghanistan Picture Show: Or, How I Saved The World; Poor People; Riding Toward Everywhere; The Book of Dolores.