The Purpose of a Counterculture

For every mainstream interest there runs a counterculture parallel to it.

A counterculture will – as is evidenced by the name – reject their contemporary mainstream society, opting to develop an alternative that better represents those disillusioned by the social, political, and cultural landscape of their time.

Take, for example, the Surrealism movement of the 1920s. Spearheaded by Andre Breton, surrealist art had aimed to reject the traditional order through painting and writing that focused on the internal and subconscious thought. This new style had been coaxed into and out of a generation sent into the trenches during WW1 and who returned questioning the old views and values of those who had sent them there.

Another example could be found thirty years later with The Beat Generation. In a similar manner, this generation was motivated by what they had witnessed during war times – the difference being was that this was WW2 instead. Pinnacle figures of the Beats like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, sought to take a different path to the nuclear family-esq expectations of their contemporary society.

The beats soon made way for the likes of the swinging sixties and that soon evolved into a more aggressive and abrasive reaction in Punk. I could go on...

The point being is that a counterculture aims to highlight contemporary problems through what they reject. Whether the counterculture’s main aim is to subvert an art style, develop a new way to live life, or bring people together to oppose a great injustice, countercultures are nonetheless integral in providing a voice for those who cannot relate to the status quo.

Yet whilst the aim remains the same, the counterculture does not. Such as the mainstream morphs and forms throughout the decades, so do the countercultures. Like a yin to a yang.

Time does wonders for these countercultures. With perspective granted to those looking over their shoulder, a counterculture’s influence could far exceed that of the mainstream it had run parallel to and often we see echoes of that influence within the current society we are in. Accordingly, these countercultures are viewed in a more favourable light in retrospect.

But unfortunately, not all attempts at rebellion are seen with any level of respect whether in their time or afterwards. Sometimes the act of going against the grain produces within its mainstream defectors the thrill of going all the way with its outward revulsion. Sometimes things go a little too far. Sometimes certain art styles get created that should have never seen the light of day.

We’re not talking the abstract weirdness of surrealism, or the swinging sixties’ heavy substance abuse in the name of flower power, or the subversive safety pin snarls of a simplified rock n roll in Punk rock. No this is much more abrasive, confrontational, and offensive, for I am talking about a counterculture that reaches Sade-level shock value in the form of the written word - a counterculture that aimed to do nothing but disgust, shock, and offend… and it achieved all three and more.

Despite this, however, the counterculture I am speaking of is not so well known. Fortunate for those with a weak stomach, it appeared as quickly as it vanished, and even now people don’t seem to know much about this brief period in time when confronting the worst of human nature through the written word was in vogue.

This is the disturbing rise of Splatterpunk.

Context Of The 1970s and 1980s

Our story begins with a little historical context. Particularly, the state of the UK and the US in both the 1970s and 80s.

In regards to the former, the UK was in trying times. For the first time since the end of WW2, the UK had begun to fall behind their contemporaries economically. Culturally the artistic landscape was dull until the back end of the 1970s and into the 1980s when things began to pick up with the arrival of Punk and New Wave. Additionally, protests were occurring all around the country and the IRA were causing mass anxiety for the population. To top it all off, by the end of the 1970s Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister and would remain so throughout the following decade.

On the other side of the pond things weren’t looking too great either. The 1970s were the depressing hangover of the swinging sixties. What had not long before seemed rife for change and idealism had died off into a conservatism and conformity that appeared to reach its max with the Nixon administration, occurring between 1969 – 1974, and continued with the Reagan administration which started in 1981.

The Richard Nixon Presidential Library summed up the 1970s as such:

“The seventies were an uncertain time. The United States was powerful and wealthy, but Americans were uneasy, struggling with unemployment, inflation, and a series of energy crises. As the nation transitioned from a manufacturing to a service-based economy, plants closed, workers protested, and jobs went elsewhere. A mass movement questioned the environmental costs of American affluence. Reforms meant to alleviate poverty and promote economic vitality stalled.” - The Richard Nixon Presidential Library, 1970s America.

The uncertain times seemed perfect for a resurgence of the horror genre. In the 1970s staples of the genre were being published such as The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty (1971) and Stephen King’s Carrie (1974), the latter of which would give the ascending trend boosters into the mainstream.

Slasher films too were on the rise. With films like Friday the 13th, Halloween, and Nightmare on Elm Street capturing the dark imagination of the everyday man and woman, horror – with all art styles considered – was at peak popularity. The genre hadn’t had so many notable names attached to it since Edgar Allan Poe or HP Lovecraft.

Of this surge in popularity, a subsect of horror would be found in “quiet horror” - a style that aimed to scare its readers through suggestibility and suspense. The term quiet horror came from Stanley Ellin’s 1965 short story collection of the same name. It would be further popularised by writers such as Ramsay Campbell and Charles L Grant.

And so now we have the scene. Political conformity, social unrest, and a horror boom. Scenes such as this were going to break out in many forms, however, in our particular niche, this configuration broke out in a term coined at a party in 1986 by writer David J. Schow following a heated debated against those on the side of quiet horror and those siding with a more explicit style the name of which they hadn’t quite got right yet.

What Is Splatterpunk?

At its most basic explanation, Splatterpunk is a movement in the horror genre that sought to portray its horror elements in as unflinching and graphically descriptive a way as possible. No suggestibility or filling in the blanks here, if someone in a Splatterpunk novel has to die you are going to read the gruesome details of it.

Elements of Splatterpunk can be traced back to many artistic mediums throughout the decades, but its generally agreed that it truly formed into a style in the 1980s. Particularly 1981, when Splatterpunk-esq stories began appearing in the magazine The Twilight Zone, published by Rod Sterling.

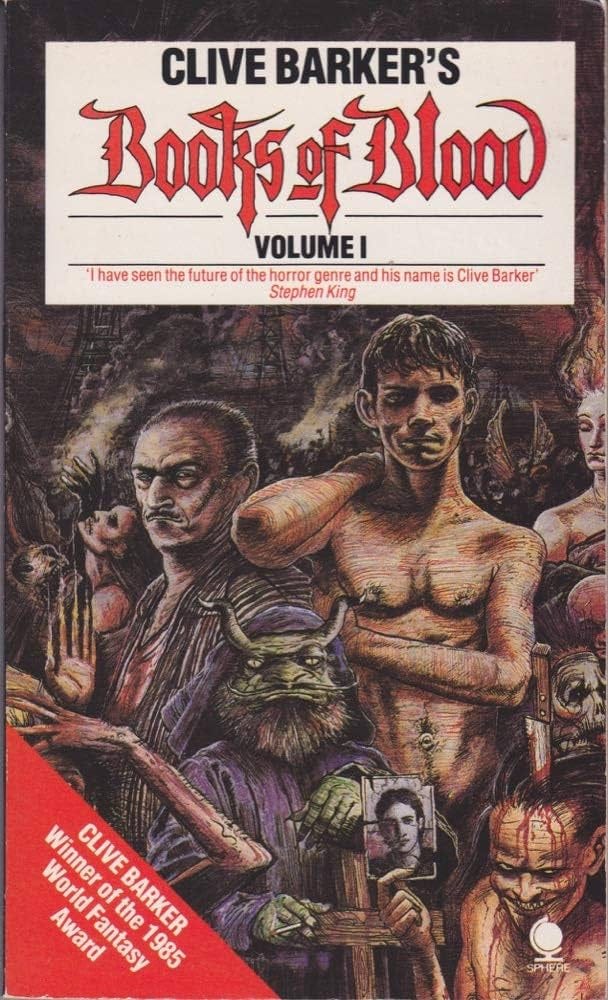

Despite the rumblings of this new style making small waves in the literary scene, Splatterpunk wouldn’t officially reveal itself until the publication of two notable books: Books of Blood by Clive Barker and The Light at the End by Craig Spector and John Skipp.

The former is a collection of short horror stories that propelled Barker into an incredibly successful writing career. The collection contains sixteen stories with titles such as “The Midnight Meat Train”, “The Skins Of Our Fathers”, and “Human Remains”, to name but a few.

Books of Blood was classic Splatterpunk despite the term not having been coined at the publication of the book. The stories were to the point, confrontationally violent, sometimes erotic, and containing a deeper undertone to the madness that I will elaborate on later.

The latter book is itself a singular story. The Light at the End is a similarly unflinching piece of Splatterpunk literature. In short, the story is set in New York City and features a person called Rudy Pasko who – after being bitten by a vampire on a subway train – goes on a murdering spree of his own.

It could be argued that Clive Barker, Craig Spector and John Skipp are at the top of the Splatterpunk writer hierarchy. However, there were many others who deserve a mention. Writers such as David J Schow, Joe Lansdale, Jack Ketchum, and Robert R McCammon to name a few.

To pre-empt the rolling eyes of Splatterpunk fan’s eyes, I understand that some of the names on this list either dipped in and out of Splatterpunk or just had elements of Splatterpunk in their work. Some names just listed would maybe even be offended at the notion of them being deemed a Splatterpunk. I will get to that later.

For now, just know that these names were the writers of the Splatterpunk movement, a movement that rejected shying away from human being’s worst impulses. They were doing, in a sense, what writers like William S Burroughs or the Marquis de Sade were doing in their time:

“These are the renegades, the edge walkers, the dwellers in the abyss; uncompromising artists whose inner eyes see bitter truths. They are the dark magnets to which we are drawn, attractors/repulsors who understand the allure of outrageousness. They are the epitome of black humor, stand-up comics for the apocalypse. And their fiction sweeps across the page like hot actinic searchlights, probing the darkest corners of our souls. They are, in a word, Splatterpunks.” - Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. XIII

This quote accurately portraying the ballsiness of Splatterpunk writers is from Paul M. Sammon. In his time, Sammon achieved a lot as a journalist and focused primarily on producing articles and books dedicated to his love of film and literature. Some notable releases include Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner (1996), The Making of Starship Troopers (1997), and Conan The Phenomenon (2007). Despite film being the main attraction, another work he has produced is the first ever comprehensive guides to understanding Splatterpunk.

Released in 1990, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror is a great introduction to Splatterpunk due not only to the fact that it contains seventeen short stories from the quintessential writers of the movement, but also because it contains the fifty-page long essay titled “Outlaws” in which Sammon aims to explain the who, what, when, where, and whys of this violent literary style.

In this essay we are given the basic details of Splaterpunk that I have already shared: when it is generally thought to have begun; the essential writers; the name’s origin etc. But we are also given insight into why people enjoyed Splatterpunk in the first place.

Splatterpunk’s allure, Sammon says, can be broken down into two levels:

The first level is catharsis. In a somewhat similar vein to slasher movies, Splatterpunk appeals to an audience’s darkest fantasies. Unexpectedly, the horror genre sparked outrage among the mainstream book lovers, however, Sammon saw Splatterpunk as a tool to roughen up the imagination. It allows audiences to lose themselves in a senseless fantasy that held no boundaries. To stretch out the mind, so to speak.

The second level, however, went deeper than the surface level violence for the sake of violence, and argued for Splatterpunk’s ability to – through its naturally confrontational style – address social and/or philosophical issues:

“At its best, Splatterpunk is a literature of confrontation, anger, and despair, sometimes flirting with nihilism but always aware that it is using materials from the real world as its fabric. In this arena, Splat becomes political and cautionary; there are horrors out there, within and without you, and they really can hurt you.” - Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 281.

Unlike the prevailing slasher movies of the 1980s, Splatterpunk tried to be something deeper. To the Splatterpunks, films like Friday the 13th were nothing more than watching the movie’s creator try to find increasingly creative ways to kill its victims. In other words: the allure of slasher movies stopped at the first level.

Splatterpunk, on the other hand, was attempting to almost mock that catharsis whilst bringing a catharsis of its own – but with a deeper meaning. It wanted to shove the most debased instincts of humanity in the face of its readers, hoping to – through forced acknowledgment – create and/or promote change. Unfortunately for them, the average reader did not always see it this way, and neither did the contemporary horror establishment:

“[…] while most would assume that successful practitioners of a field of literature that indulges in terror, violence, and imagination would be of the utmost liberal stripe, the exact opposite holds true. The horror establishment, like its science fictional counterpart, is basically conservative. Science fiction and horror fans are notoriously resistant to change; Spock can’t die, Jason must wear a hockey mask, and so on. So, it’s not surprising that the reaction by the horror establishment to Splatterpunk was, at best, one of pained silence […]” Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 285

And so, the counterculture of Splatterpunk was not only rebelling against the everyday social and political status quo but also the – as they saw it – similarly averse-to-change-stick-up-the-arse old fuddy duddies of those at the top of the horror world.

But enough skirting around the topic: now it’s time to present a Splatterpunk story.

The Midnight Meat Train

When attempting to find a story that best encapsulates Splatterpunk I was at a loss. There are many examples with no standout to use. Therefore, I thought best to provide a condensed short story that you could go and read for yourself to decide whether this particular type of horror is for you.

I’ve got to be honest, when I first heard about Splatterpunk I immediately judged it as something stupid. I was introduced to the genre through a friend who suggested it for a video topic, and as I gave it a quick google and read its wiki, naturally I saw components necessary to create a video with a topic rife with potential for mockery, shock value, and sensationalism.

Yet, as I have researched beyond the wiki, placed my preconceived notions aside, and read some Splatterpunk, I get the appeal. Maybe not to the extent of some, but I get it.

Splatterpunk is never going to be a personal favourite of mine, however, I did get some enjoyment out of these stories. The first one that clicked with me I want to share (spoilers ahead). Whether through the first or second level of allure, I think the fence sitter could be coaxed to the side of Splatterpunk by the previously mentioned twenty-seven-page short story “The Midnight Meat Train”.

Written by Clive Barker, The Midnight Meat Train is a scathing commentary on the New York of the 1980s. It tells the story of New York resident Leon Kaufman, whose unexpected transition from everyday New Yorker to the servant of the cities’ underworld changes his perception of the city forever.

We are introduced to Kaufman as a three-and-a-half month-long New Yorker who, in such a short space of time, is disillusioned with his environment. Seeing New York as The Palace of Delights in his youth, he had come to the city with high expectations of the glamour and excitement he believed only The Big Apple could bring to his life.

When he arrived in the city, he did so with an idealism so strong he looked up to the sky and loudly proclaimed “New York, I love you!”

Unfortunately for Kaufman this was the New York of the 1980s, rife with criminal activity and in need of a tidy. The idealised version of the city in Kaufman’s mind is likened to the idolisation of a seemingly clean-cut woman who turns out to be the opposite:

“New York was just a city. He had seen her wake in the morning like a slut, and pick murdered men from between her teeth, and suicides from the tangles of her hair. He had seen her late at night, her dirty back streets shamelessly courting depravity. He had watched her in the hot afternoon, sluggish and ugly, indifferent to the atrocities that were being committed every hour in her throttled passages.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 19.

Kaufman’s first three and a half months in the city brought him into contact with many dangerous scenarios and people who shared similar stories. Creepy looks, late night fast paced walks home, eyes constantly over his shoulder. But nothing could quite compare to the murders occurring below, in the subways. “Subway slaughter” was the term being used by the residents and the press. It was a weekly occurrence, and nobody knows who or why.

Enter Mahogany: the answer to those questions. When we are introduced to the butcher, he is just waking up in his dingy flat high above the potential victims next to be chopped up and hung upside down, carved up as if for an elaborate meal.

Mahogany views himself as a higher being. He looks at the population as a human butcher would: as cattle. When he looks from his window at the people filing in and out of buildings or others absentmindedly walking within larger crowds directing towards nowhere important, he does so with a satisfaction at their ignorance towards his importance.

Despite his innate brilliance, Mahogany knows he is getting old. His age has led to sloppy work, and by sloppy work, I mean jobs half done and/or abandoned due to the cops being on his tail. His evasive abilities have diminished due to his age. Soon he would need to pass on his knowledge before he gets too old to continue:

“There were so many felicities he could pass on. The tricks of his extraordinary trade. The best way to stalk, to cut, to strip, to bleed. The best meat for the purpose. The simplest way to dispose of the remains. So much detail, so much accumulated expertise.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 25.

On this seemingly ordinary night Kaufman and Mahogany were working late: the former at the office, the latter on the Avenues of Americas line. Both were to come into contact soon enough.

After a late-night session that Kaufman promised himself would be over by 10pm, 11pm had struck and he hadn’t even finished his work. Fatigued and with no clear end in sight, Kaufman mumbled a “fuck it” under his breath and left the office to catch the last subway home.

He got on the train and sat in the first car. To his right in the second car a spotty adolescent sat staring up at the graffiti on the ceiling along with some other passengers further down. Knowing he had thirty-five minutes before arriving at his stop, Kaufman drifted off to sleep – a sleep ushered on by the gentle rocking of the train as it sped underneath New York. Mahogany began his butchering throughout the cars.

When Kaufman randomly awoke, he was alone in the car, which was now drastically faster than it had been prior. Darkness had descended too and to his right the second car had been curtained off. Driven by confusion and curiosity, he got up and tried not to lose balance as he tried to get a peek through the curtain. He slipped up on blood. He then found a small rip in the curtain he used to get a look into car two:

“His mind refused to accept what his eyes were seeing beyond the door. It rejected the spectacle as preposterous, as a dreamed sight. His reason said it couldn’t be real, but his flesh knew it was. His body became rigid with horror. His eyes, unblinking, could not close off the appalling scene through the curtain. He stayed at the door which the train rattled on, while his blood drained from his extremities, and his brain reeled from lack of oxygen. Bright spots of light flashed in front of his vision, blotting out the atrocity. Then he fainted.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 31.

Kaufman awoke on the floor lodged underneath the seats of the train. Fortunately, the increased speed of the train, and thus its rocking, nudged him out of sight of Mahogany, who had entered car one and went straight to the driver to strike up a conversation.

As Mahogany was lost in whatever conversation he was in with the driver, Kaufman begins to edge towards the door to car two in hopes of escaping a similar fate to what he saw through the curtain. Knowing what he would have to confront on the other side, Kaufman crawls to the door, grips the handle, and slips inside, now face to face with the work of the butcher:

“It filled every one of his senses; the smell of opened entrails, the sight of the bodies, the feel of fluid on the floor under his fingers, the sound of the straps cracking beneath the weight of the corpses, even the air, tasting salty with blood. He was with death absolutely in that cubbyhole, hurtling through the dark.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 34.

The hanging and mutilated bodies of the adolescent along with two women and another older looking male were swaying to the rock of the train. Despite this, Kaufman knew he had to keep moving forward to put as much distance between him and the butcher as possible.

As he was doing so the train suddenly rocked violently and the lights momentarily switched off. Kaufman fell and reached out to grab on to something. And he did: to the back muscles of one of the hanging corpses with his face following seconds after. In pitch black and the wet meat between his fingers, he screamed.

The lights came on. Rapid footsteps could be heard from the first car. In less than five seconds Kaufman was now face to face with Mahogany. A few words were exchanged as Mahogany slowly crept forward with his cleaver in hand. He swung and missed Kaufman’s face by an inch. The cleaver lodged into one of the corpses, and – taking his chances – Kaufman plunged a knife he found on the floor into Mahogany’s neck.

After a tense second or two, the knife was pulled out and Mahogany clawed at his neck as death came for him undeterred by Mahogany’s desperate attempts to thwart it away:

“Mahogany collapsed to his knees, staring at the knife that had killed him. The little man was watching him quite passively. He was saying something, but Mahogany’s ears were deaf to the remarks, as though he was underwater. Mahogany suddenly went blind. He knew with a nostalgia for his senses that he would not see or hear again. This was death: it was on him for certain.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 38.

Following his kill, Kaufman stood staring at the dead butcher and his victims strewn around the car. As he did so the driver announced their arrival and the train slowed down to a stop in darkness.

Silence descended on the train. Then, the doors opened, and footsteps could be heard coming closer. The odd light flicker reveals multiple heads outside the train shuffling in Kaufman’s direction. One light lingers a little longer and gives Kaufman enough time to see a throng of frail, pale, bald men, and women walking zombie-like towards the hanging corpses, eager to take a bite. Kaufman picked up the cleaver.

One of the things spotted Kaufman and drew a light on his face. The things surveyed the situation, noticing Mahogany’s body on the floor, and realised they had a new butcher.

The leader of the men/women approached Kaufman and explained who they were: the fathers of New York. They built this city. Without their survival New York would cease to exist. They were its builders, lawyers, and congressmen – they were everything.

Kaufman was told he was now to pick up where Mahogany left off: he would bring them human meat every week to ensure their survival. He would serve them.

Initially refusing, the leader then pointed out the car window towards a less human looking silhouette waiting outside. Pulled by an invading instinct to worship his feet took him to the outside of the train to see this form for himself. Slightly illuminated by torch lights, the thing before him creaked and shifted. Kaufman was staring at the father of fathers:

“It was a giant. Without head or limb. Without a feature that was analogous to human, without an organ that made sense, or senses. If it was like anything, it was like a shoal of fish. A thousand snouts all moving in unison, budding, blossoming, and withering rhythmically. It was iridescent, like mother of pearl, but it was sometimes deeper than any color Kaufman knew, or could put a name to.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 43

Reverence overtook Kaufman and he lifted to his feet. The leader came over to him, took his face in his hands, and made Kaufman stare at himself through the reflection of the train window. “Serve us?” the leader asked before reaching into Kaufman’s mouth, grasping his tongue, and ripping it out.

Kaufman tried to scream as the ancients threw him back on to the train and retreated into the darkness with meat in hands. Kaufman, once again, fainted.

The driver woke Kaufman up at an unknown pristine white station. Kaufman was then directed towards an exit that took him to street level. Looking around him, Kaufman viewed New York with new eyes. The idealism he had once felt for the city had for the first time become a reality. He would thank his newfound appreciation through service to those who built the city: the fathers:

“It was a beautiful day. The bright sky over New York was streaked with filaments of pale pink cloud, and the air smelt of morning. The streets and avenues were practically empty. At a distance an occasional can crossed an intersection, its engine a whisper; a runner sweated past on the other side of the street. Very soon these same deserted sidewalks would be thronged with people. The city would go about its business in ignorance: never knowing what it was built upon, or what it owed its life to. Without hesitation, Kaufman fell to his knees and kissed the dirty concrete with his bloody lips, silently swearing his eternal loyalty to its continuance. The Palace of Delights received the adoration without comment.” - Clive Barker, Paul M. Sammon, Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, P. 45

The Decline of Splatterpunk

Despite Paul M Sammon’s anthology coming out at the beginning of the 1990s as well as a follow up published in 1993 titled Splatterpunks Two: Over The Edge, the genre took a nose dive in popularity with the arrival of the new decade.

That is not to say that people stopped writing Splatterpunk stories, however, the general appeal of the genre seemed to wear off. The reasonings why are not so confidently documented, but I have some theories of my own that I would like to share.

The first was that the writers often didn’t like to be associated with Splatterpunk. Sammon comments on this. When piecing together the first anthology he would contact those he aimed to include in his book, doing so to get their permission. Often, Sammon was given the permission but under the condition that they are not portrayed as a Splatterpunk writer. Sammon would agree and preface their stories as being an example of Splatterpunk elements being implemented rather than the work of a full-fledged writer of the genre.

The reason for this was because to be coined a Splatterpunk writer was to – in the eyes of the general population – indirectly discredit your writing abilities. It was seen as the equivalent of a director being an adult entertainment director, sure they can do the job but the job itself is the lowest effort there is.

The connotations of Splatterpunk at that time – and really even now – degraded the level of seriousness that writer would be taken at. Making a living as a writer is difficult enough and these people wanted to preserve their careers. Rejecting the term was a way to do so.

The second blow to the longevity of Splatterpunk was the introduction of the term “extreme horror”. Extreme horror was essentially what the average joe thought Splatterpunk was: mindless violence. Whilst Splatterpunk used its unflinching nature to attempt to address societal issues, extreme horror was satisfying that level of catharsis inherent in those who want violence for violence’s sake. The public were not privy to this so lumped the two together. With these lines being blurred, the already niche genre was fragmented even more than it had been previously.

Another reason for its decline was the fact that there was no one person who led the charge. Unlike in the other countercultures mentioned earlier in this video, Splatterpunk did not have what Andre Breton was to surrealism, or what Ken Kesey was to the swinging sixties, or what John Lydon was to punk. All they had were fragmentedly placed stories within a loose community, half of which, rejected the name anyway.

Lastly, Splatterpunk didn’t have its own style. It didn’t have a thing. The issue was, was that Splatterpunk didn’t have an aesthetic that distinguished it in the same way something like Cyberpunk did. We hear cyberpunk and picture the typical aesthetic, but with Splatterpunk we can’t because there isn’t one besides gore – and to get to the gore you need to read it. A Splatterpunk book could easily be mistaken for any horror book from the outside.

And so, with all that being said, the genre simply fizzled out in its relevance. In the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s the genre was practically dead. It was only until the 2010s that the genre began to make a resurgence.

Splatterpunk Resurgence?

As previously mentioned, when I was first introduced to Splatterpunk it was through a friend who had found it on TikTok.

It seems as if the genre has met a new generation of gore lovers wanting to read something that aims to shock and awe with its grotesquery. So much so in fact, that in 2018 a Splatterpunk awards was founded by two men called Brian Keene and Wrath James.

The more recent Splatterpunk books have attached to themselves somewhat of a reputation not unlike those of the 1980s. Just by putting “I read X” (X being one of the more recent Splatterpunk books) in the title of a video will guarantee views due purely to those familiar with the work wanting to see how others react to the content.

Books like The Slob and Playground by Aron Beauregard are two common examples. With the internet, independent publishing has flourished thus allowing authors to have more freedom to title their books whatever they want as well as to be able to put whatever they want on the cover. One of my favourite examples of this freedom is in the elegantly titled I’ll Fuck Anything That Moves And Stephen Hawking by wordsmith and poet Violet Levoit.

There is debate as to whether the books just mentioned lean more towards extreme horror than they do Splatterpunk. Sometimes this can be hard to define, as the lines that separate the two – as previously mentioned – are blurred. Additionally, meaning is within the eye of the beholder. It is ultimately for you to decide.

Comforting The Disturbed

The purpose of a counterculture is to provide an alternative way of being. Within this parallel system, a counterculture provides a meaningful reflection of what is wrong with a society. In doing so, a representation is created for the disenfranchised. Hope of changes naturally follows along.

Cesar A. Cruz said it best when he wrote this sentence on the purpose of art:

“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” - Cesar A. Cruz

I think that quote best encapsulates what Splatterpunk was trying to do. The people most negatively impacted by the hard times of the 1970s and 80s were being represented in some small way via the literary horror genre of Splatterpunk. Call it what you want, but the aim was every much as valid as were the aims of the surrealists of the 1920s, the beats of the 1950s, the hippies of the 1960s, or the punks of the 1970s: it was all a mode of expression that served as a monumental fuck you to the face of a society that they felt let them down.

I wonder how the next counterculture will deal with our times…