The Death of Osamu Dazai

On the 19th of June 1948, two bodies were discovered in a section of a 43-kilometre-long stretched aqueduct located in Tokyo, Japan, called the Tamagawa Canal. On the edges of the canal stood a crowd gathered around the two bloated bodies – now six days old - trying to get a glimpse whilst the authorities fished them out.

The news of the names identified to these bodies shocked the population, but not those with any understanding of these two people prior to their fate. The first body was identified as a woman by the name of Tomie Yamazaki, the soon-to-be-labelled “lover” of the second body lying beside her.

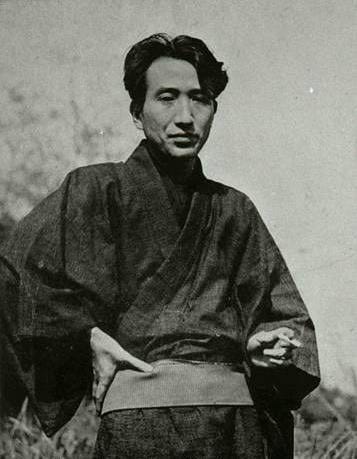

That body was Osamu Dazai, a popular Japanese author who had released a novel hailed as his masterpiece not long before this final act. The novel itself would, in retrospect, displayed the tormented mindset behind his decision.

Osamu Dazai’s life was one of indulgent tragedy, a series of negative factors taken to their sadly predictable conclusion. Throughout his life, Dazai had suffered with an assortment of mental health issues, societal issues, familial issues, and substance abuse issues. Additionally, he was the type of author to rely on his own life for his literary content, and so, almost every book’s content and tone reflected his mindset at the point of time in which it was written.

Unsurprisingly, his final book’s tone was darker than ever before. It is a hopeless, bleak, and exhausted display of a life spent in alienation and shame. This would be published mere months prior to the 13th of June 1948, the day Osamu Dazai and Tomie Yamazaki took their lives together.

The book left behind has since been viewed as a goodbye note, and seventy-six years later, people are still picking up this classic of Japanese literature – it is one of the best-selling books to ever come out of Japan.

It goes without saying that, of course, Dazai’s final novel can be appreciated without the morbid context surrounding it. However, what we all cannot avoid when reading the book is an acknowledgement that this tragic tale is also a confession - a confession of the inability to participate in society, a confession to feeling disqualified as a human being, a confession to being…

No Longer Human.

No Longer Human

No Longer Human tells the chaotic life story of Yozo Oba beginning in childhood and ending, well… we’ll get there…

Told through three notebooks discovered by an unknown narrator, we watch the slow disintegration of Yozo’s mental and physical health as he trudges through a reality that appears designed only to confuse and frighten him.

The book includes a prologue and epilogue in which our nameless narrator guides the narrative. In the prologue our narrator details his reasoning for his intrigue in the notebooks as coming from three photographs of Yozo he found that unnerved him.

The first photograph depicts Yozo as a young boy grinning in a manner that was, to say the least, unconvincing:

“[…] the more carefully you examine the child’s smiling face the more you feel an indescribable, unspeakable horror creeping over you. You see that it is actually not a smiling face at all.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 14.

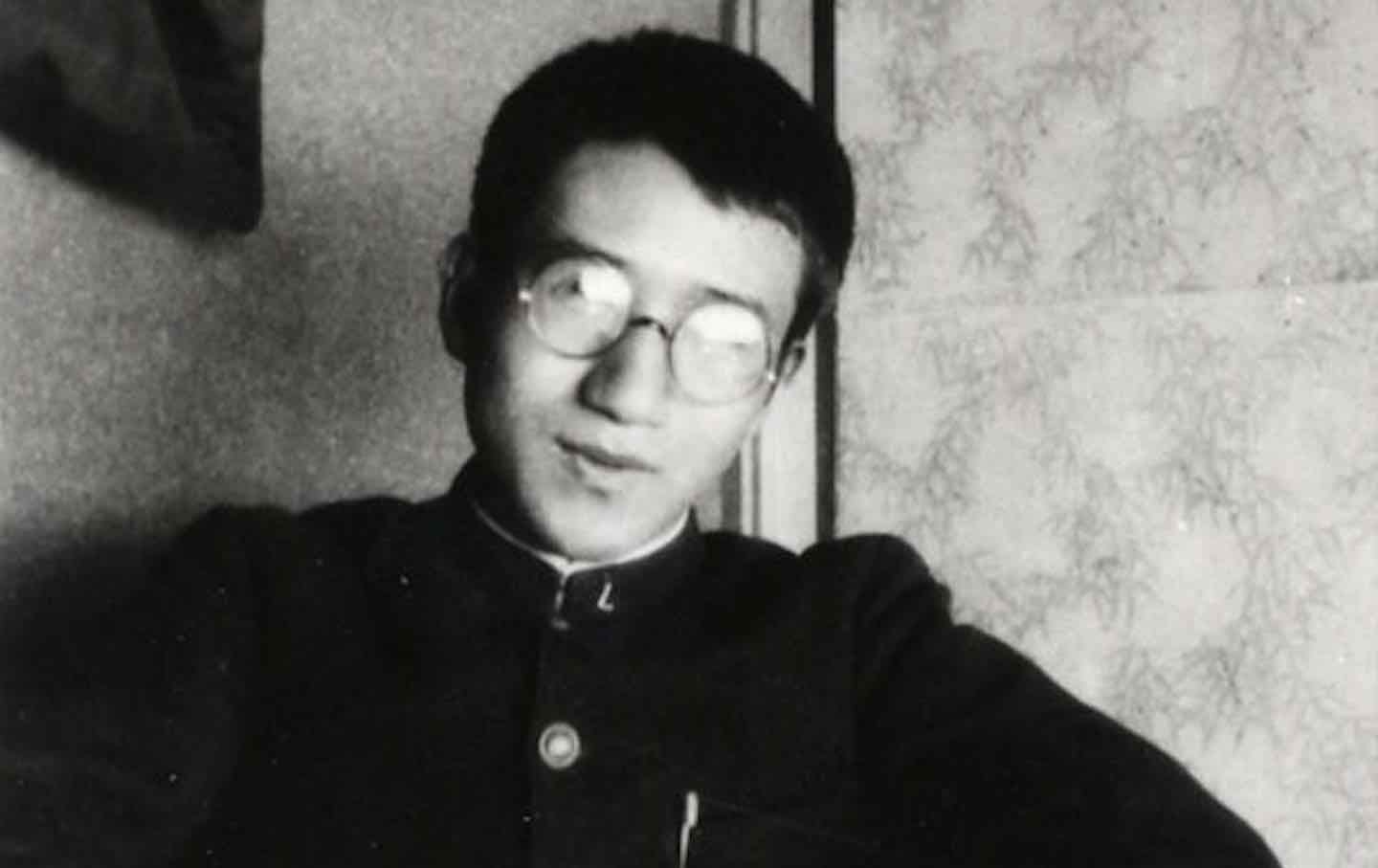

The second photographs contains Yozo as a student. One notable aspect of Yozo is his striking features. He was a handsome man. Despite this, and despite the many elements of Yozo proving his human identity in this second photo – his clothing, his smile, his body, his crossed legs, etc. – the narrator once again sees someone who is not quite what he appears to be. That same smile still seems… disingenuous.

“Again he is smiling, this time not the wizened monkey’s grin but a rather adroit little smile. And yet somehow it is not the smile of a human being: it utterly lacks substance, all of what we might call the ‘heaviness of blood’ or perhaps the ‘solidity of human life’ – it has not even a bird’s weight.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 15.

The last photo relayed to us by this nameless narrator is the most harrowing of all. Once again, Yozo is depicted, but this time he is not a seemingly healthy-looking individual covering up an emptiness with a grin. No, this time all we see is a monster – or at least, what is perceived to be a monster. The darkness desperately covered up by smiles in the former two photographs is now wearing itself on Yozo’s visage for all to see. He is seen in the corner of a room, hair grey, no expression – a shell. It was like looking at an abyss. He was the type to not leave a bad impression, but none at all.

“I think that even a death mask would hold more of an expression, leave more of a memory. That effigy suggests nothing so much as a human body to which a horse’s head has been attached. Something ineffable makes the beholder shudder in distaste. I have never seen such an inscrutable face on a man.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, PP. 16 – 17.

It is here where we are introduced to the first of three notebooks. Our introduction into the mind of Yozo begins with one chilling line:

“Mine has been a life of much shame.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 21.

The first notebook details the childhood of Yozo. We are introduced to his wealthy family, where he was born (a village in the Northeast of Japan), and his inability to connect with or understand people.

Yozo makes it clear off the bat that he cannot relate to other people. To him, humans were these creatures who seemed prepare to strike out at the slightest provocation or order disobeyed. This apprehension within Yozo generated an ambient anxiety within – an anxiety he quells through a technique he picked up from a young age and that he would carry with him into adulthood:

“All I feel are the assaults of apprehension and terror at the thought that I am the only one who is entirely unlike the rest. It is almost impossible for me to converse with other people. What should I talk about, how should I say it? – I don’t know. This was how I happened to invent my clowning.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 26.

Yozo’s clowning would become one of the many masks he would develop in his lifetime. Born out of his fear of others and what they may do should he disobey them, Yozo used his “clowning” to ingratiate himself into whatever collection of humans he needed to.

Clowning kept the potential critiquing of others at bay. The thought of any human being imparting a syllable of disapproval on to Yozo broke him out into a sweat. Yozo did not view a “telling off” from a parent as an attempt at an adult to discipline a child, but instead viewed it as some wild animal in human clothing revealing its inhuman form before recoiling back to a civilised human being.

Another purpose of the clowning was to hide in plain sight. Through being the family jester, slapping his fraudulent smile in every photograph imaginable, and continually improving upon his joviality with props, Yozo successfully kept his true thoughts and feelings below radar. He was the kid who was known for always smiling, joking around, and making everyone laugh – and that’s what he wanted, as it prevented anyone from ever sincerely conversing with him face-to-face.

“I thought, ‘As long as I can make them laugh, it doesn’t matter how, I’ll be all right. If I succeed in that, the human beings probably won’t mind it too much if I remain outside their lives. The one thing I must avoid is becoming offensive, in their eyes: I shall be nothing, the wind, the sky.’ My activities as jester, a role born of desperation, were extended even to the servants, whom I feared even more than my family because I found them incomprehensible.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, PP. 28 – 29.

Yozo thus continued his childhood and adolescence playing the fool. He would routinely view every interaction as an act on his behalf. Whether a random person, family member, friend (I say that in the loosest way possible), or lover (once again: very loosely), Yozo’s role within any given dynamic is singular. A two-person interaction is not a mutual transition of pleasantries and connections, but one person innocently seeking an affinity and another deceptively projecting what he thinks they want to see: a clown.

But not everyone is so easily deceived. In the second notebook we witness the first instance of someone taking off Yozo’s mask and the subsequent fear it produces.

Whilst in high school, Yozo’s clowning had successfully concealed his true self, and in the process, made him a beloved member of his class. Everyone appreciated Yozo’s humour… except for one student.

One day whilst in a physical education lesson, Yozo had once again been clowning by jumping for a pull up bar and purposefully missing it so as to fall straight on his back and get a laugh. After doing this, standing up, and brushing the dust from his trousers, he felt a tap on his back. Turning around with a plastic grin he faced the cold face of Takeichi (the only member of the class who was never impressed with Yozo’s clowning) who said, “You did it on purpose”.

Yozo immediately went into shock.

“I trembled all over. I might have guessed that someone would detect I had deliberately missed the bar, but that Takeichi should have been the one came as a bolt from the blue. I felt as if I had seen the world before me burst in an instant into the raging flames of hell. It was all I could do to suppress a wild shriek of terror.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 44.

Takeichi is the first example of many of the one-sided relationships in Yozo’s story. From this day onwards, Yozo sticks close to Takeichi in order to keep an eye on him. However, despite Yozo’s daily socialising with Takeichi occurring purely down to Yozo’s personal gain, the “friendship” did offer one element of never before felt happiness for Yozo. This occurred during a day in which the two were hanging out at Yozo’s house. Takeichi had brought along with him a colourful painting that he displayed to Yozo with the line:

“It’s a picture of a ghost.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 52.

Takeichi was holding Van Gogh’s self-portrait. The displaying of this photo did not so much show Yozo a work he had never seen before, but instead, re-contextualised the viewpoint from which he had looked at art:

“There are some people whose dread of human beings is so morbid that they reach a point where they yearn to see with their own eyes monsters of ever more horrible shapes. And the more nervous they are – the quicker to take fright – the more violent they pray that every storm will be… Painters who have had this mentality, after repeated wounds and intimidations at the hands of the apparitions called human beings, have often come to believe in phantasms – they plainly saw monsters in broad daylight, in the midst of nature. And they did not fob people off with clowning; they did their best to depict these monsters just as they had appeared. Takeichi was right: they had dared to paint pictures of devils. These, I thought, would be my friends in the future. I was so excited I could have wept.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, PP. 53 – 54.

Yozo had thus found his outlet. He began painting self-portraits almost immediately and would routinely show them to Takeichi. These self-portraits revealed the unmasked Yozo and it was only Takeichi who he would allow to see them. Takeichi would continually encourage Yozo to keep painting, as he believed him to be incredibly talented.

With his new passion, Yozo wanted to enrol in an art school. However, terrified by his father’s potential lashing out at the suggestion of a diversion from his grand plans for his son, Yozo never mentioned the idea, and obediently allowed himself to be sent to a college in Tokyo.

It was within this environment where Yozo was introduced to quite possibly all of the worst things for a person of his disposition to be exposed to, and it was all thanks to one Masao Horiki – an art student:

“Before long a student at the art class was to initiate me into the mysteries of drink, cigarettes, prostitutes, pawnshops, and left-wing thought. A strange combination, but it actually happened that way.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 58.

Horiki would become the second friend of Yozo. Much like the one-sided dynamic of Yozo and Takeichi, Yozo’s “friendship” with Horiki was built upon Yozo’s ability to passively allow others to talk at him without complaint. More importantly though, the two’s relationship was built on alcohol.

The two met when Horiki asked Yozo for five yen. Afraid to say no, Yozo complied and the two went drinking. As they drank and Horiki spoke towards our noble protagonist, the numbing effects of alcohol began to take place within Yozo. He described it as a:

“[…] lightness of liberation.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 59.

It is through Horiki that Yozo is exposed to women. The act of being exposed to women isn’t the issue, however, when you’re Yozo, it apparently is. Takeichi prophesised around the self-portrait phase of Yozo’s story that, “Women’ll fall for [him]”.

Yozo passes through what he refers to as his apprenticeship in women through continuous visits to brothels. Somehow, this commitment soon brought out in him the aura of a “lady-killer” (his words). Unending attention from the opposite sex was terrifying and painful for our Yozo. Whether they be neighbours, waitresses, shops assistants, generals’ daughters, whatever, women gravitated towards our Yozo like zombies to human meat:

“But it was an undeniable fact, and not just some foolish delusion on my part, that there lingered about me an atmosphere which could send women into sentimental reveries.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 65.

Yozo’s relationship with women would end tragically multiple time and in a multitude of ways throughout the notebooks. He notes earlier in the book how:

“[…] many women have been able, instinctively, to sniff out this loneliness of mine, […]” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 65.

Besides a hilarious side quest wherein our protagonist somehow accidently ascends the ranks of an underground communist party purely through agreeableness, Yozo would eventually meet one of the more meaningful people in his story: Tsuneko.

Tsuneko was two years older than Yozo and also had a husband in jail. By this point in our story Yozo had begun going to cafes and enjoying the city life on his own. Having never mastered the art of interacting with others without contracting a smile, he soon built up the courage to keep a stoic countenance – or at least, he kind of did. I’ll just let him explain:

“Inwardly I was no less suspicious than before of the assurance and the violence of human beings, but on the surface I had learned bit by bit the art of meeting people with a straight face – no, that’s not true: I have never been able to meet anyone without an accompaniment of painful smiles, the buffoonery of defeat.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 77.

Despite his buffoonery, Yozo went alone to a café on the Ginza where he met Tsuneko (he actually mentions not being entirely sure this was her name), a person whose voice calmed and assured him. Tsuneko relayed her lifestory to Yozo ending with four words that perked his ears, “I feel so unhappy”.

That night, Yozo slept as soundly with a woman as he had ever done before. He awoke a clown.

A month went by and the two never saw each other. One day, Horiki suggested the two visit a café. Horiki was complaining about being horny and was on the prowl. Spotting Tsuneko at the café bar he forced a kiss on her in front of Yozo and then disregarded her as “poverty stricken”. Yozo felt a welling up of passion heretofore never experienced and dealt with it through ordering more drinks than he could afford and getting smashed. He awoke back in Tsuneko’s room.

Noticing he was awake, Tsuneko laid down beside him and the two broached the topic of death. She then proposed something:

“She too seemed to be weary beyond endurance of the task of being a human being; and when I reflected on my dread of the world and its bothersomeness, on money, the movement, women, my studies, it seemed impossible that I could go on living. I consented easily to her proposal.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 86.

The following morning the two chose to follow through with their plan. They wandered around Asakusa and briefly visited a lunch stand when Tsuneko requested that Yozo pay for their milk. She watched Yozo open his empty wallet and innocently asked “is that all?”, which spun Yozo into a sense of shame so intense he sped up the process of the day’s task:

“We threw ourselves into the sea at Kamakura that night. She untied her sash, saying she had borrowed it from a friend at the café, and left it folded neatly on a rock. I removed my coat and put it in the same spot. We entered the water together. She died. I was saved.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 87.

The reaction of this event was one of scandal. Due to his father’s high standing, Yozo’s attempt at his own life became a newsworthy event. Additionally, Yozo was detained by the police. Whilst in custody, an injury to his lung meant he was tret with ease, and noticing his coughing garnering sympathy, he began to put it on a bit.

One day whilst sat in an office talking to a district attorney, Yozo momentarily paused his speech to cough. Seeing an ample opportunity to ham it up a bit for his own gain, Yozo threw in a couple of extra big ones for good measure. Post-cough, the district attorney, flat-faced, looked up from his desk, locked eyes with Yozo, and asked:

“‘Was that real?’” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 93.

Yozo was immediately seized by a panic reminiscent of his shock at being called out by Takeichi:

“Those were the two great disasters in a lifetime of acting. Sometimes I have even thought that I should have preferred to be sentenced to ten years imprisonment rather than meet with such gentle contempt from the district attorney.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 93.

The second notebook ends with Yozo being released from custody – the charges were waived. He dodged a potential long stint in jail, yet Yozo felt no joy.

Part one of notebook three opens with a harkening back to the two prophesies of Takeichi: that women would fall for Yozo and that Yozo would become a great artist. The former true, the latter not so much. We are also introduced to Yozo’s new living situation: a small room in the back of a house owned by his dad’s generous friend who Yozo respectfully devalues down to a mocking nickname: flatfish.

It was in this small room that Yozo perfected the art of doing nothing – no drink, no women, no painting. He stayed with flatfish for a while. However, following a painful conversation/lecture from flatfish on Yozo’s future plans – in which Yozo said he wanted to be a painter, to which flatfish laughed – Yozo ran away from his home.

Homeless and at a loss of what to do, Yozo calls on his old friend Horiki but not before reaffirming his disconnect from the world:

“Though I have always made it my practise to be pleasant to everybody, I have not once actually experienced friendship. I have only the most painful recollections of my various acquaintances with the exception of such companions in pleasure as Horiki. I have frantically played the clown in order to disentangle myself from these painful relationships, only to wear myself out as a result.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 107.

Yozo’s visited Horiki’s house for the first time. Yozo was tret to food and a warm family home. Horiki’s manner within his home was polite and affable, which felt like betrayal to Yozo who had always known the hedonistic carefree Horiki. For some reason, this ability to switch between appearances made Yozo feel even more lonely.

Not soon after their meal, Horiki was visited by a woman who worked for a local magazine. Her name was Shizuko and upon Yozo being given a telegram from Flatfish asking for his return, Shizuko offered to walk with him as her office was nearby Flatfish’s housr.

Shizuko was a twenty-eight-year-old journalist and widow (her husband died three years prior) living with her daughter Shigeko.

The two would hit it off and Yozo would become entirely reliant on Shizuko before making money drawing cartoons for her magazine. They would soon become married (Yozo is an impulsive man), and with his new stable home and income, Yozo did what any man would do when given the means to do it: buy alcohol and cigarettes:

“Without a word, without a trace of a smile, I spent one day after the next looking after Shigeko and drawing comic strips, some of them so idiotic I couldn’t understand them myself, for the various firms which commissioned them. […] I drew with extremely, excessively depressed emotions, deliberately penning each line, only to earn money to drink.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 121.

A year followed and this lifestyle continued. As the weeks flowed by Yozo’s dependence on alcohol grew stronger. He would go out drinking, sleeping with random women, and not returning home for days. To add insult to injury, Yozo then began selling Shizuko’s clothes in order to afford more alcohol.

One day in the apartment, Yozo overheard a conversation between Shizuko and Shigeko with the latter asking why “daddy” (referring to Yozo) drinks, to which Shizuko attempted to explain. The conversation was soon interrupted by a rabbit the two had been sat with, and as Yozo watched mother and daughter laugh and enjoy each other’s company, he came to the conclusion that he was only going to ruin the tranquillity they shared:

“(They were happy, the two of them. I’d been a fool to come between them. I might destroy them both if I were not careful. A humble happiness. A good mother and child. God, I thought, if you listen to the prayers of people like myself, grant me happiness once, only once in my whole lifetime will be enough! Hear my prayers.) – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 124.

Yozo left the apartment and never returned.

In true Yozo fashion, he found his way to a bar in Kyobashi, sat down at a stool, turned to a woman he knew behind the bar, and said “I’ve left her and come to you.” They moved in together.

Another year of heavy drinking and drawing cartoons ensued. Yozo had made the monumental career move of not only drawing for children’s magazines, but for adult content magazines.

The only person who ever seemed to take offence at Yozo’s excessive drinking was a seventeen-year-old girl called Yoshiko who worked in a tobacco shop. One day, outside the tobacco shop, a drunken Yozo fell into a manhole. Calling out to Yoshiko to save him, Yoshiko did just that and bandaged him up. She commented on his drinking. Yozo said he would quit drinking should she marry him. Yoshiko agreed. The next day Yozo continued drinking. They married anyway:

“Not long afterwards we were married. The joy I obtained as a result of this action was not necessarily great or savage, but the suffering which ensued was staggering – so far surpassing what I had imagined that even describing it as ‘horrendous’ would not quite cover it. The ‘world’, after all, was still a place of bottomless horror. It was by no means a place of childlike simplicity where everything could be settled by a single then-and-there decision.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, PP. 132 – 133.

Thus marks the end of the first half of the third notebook. The second half sees our protagonist at his worst.

It begins with Yozo now living with his new wife Yoshiko. Initially sober and working hard on his drawings, Yozo is paid a visit by his old companion Horiki, who – after bringing up shameful memories of the past – enables Yozo to fall back into his drinking habits. This led to the spiral with leads into the climatic tragedy of this book.

On one of the most tragic nights of Yozo’s life he was visited once again by his enabler and companion Horiki. The two did the usual and ended their drunken escapades on a roof discussing the antonyms of words. Following a debate on the correct antonym of crime, Horiki descended the stairs in search of food. He then returns seconds later asking Yozo to come and see something. Following after Horiki, the two soon appeared outside Yozo’s window where the silhouette of a man can be seen forcing himself on Yoshiko. Yozo froze in fear and ran away. His hair turned permanently grey. It was the turning point of his life:

“It was less the fact of Yoshiko’s defilement than the defilement of her trust in people which became so persistent a source of grief as almost to render my life insupportable. For someone like myself in whom the ability to trust others is so cracked and broken that I am wretchedly timid and am forever trying to read the expression of people’s faces, Yoshiko’s immaculate trustfulness seemed clean and pure, like a waterfall among green leaves. One night sufficed to turn the wakes of this pure cascade yellow and muddy. Yoshiko began from that night to fret over my every smile or frown.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 150.

This event broke Yozo. His alcoholism worsened, his appearance deteriorated, and he once again attempted to take his own life – this time, however, he had attempted to overdose on sleeping pills. He survived once again.

Yozo spent three days in a haze before coming to with Flatfish at his bedside. Yozo burst into tears and pleaded to be taken away from Yoshiko, from all women.

But he remained. Yozo’s appearance worsened, he grew skinnier by the day, he weakened, he became too tired even to draw his cartoons. Once again, he began living off of the bank of Flatfish.

On one day, drunk (of course) Yozo was walking in the cold of night and vomited up blood into the snow. Scared by the red circle encrusted in the white, he made his way to a nearby pharmacist who suggested he stop drinking. Good natured at first, this pharmacist somehow made his condition worse by supplying him with morphine – an excellent substitute!

“Without a flicker of hesitation I injected the morphine into my arm. My insecurity, fretfulness and timidity were swept away completely; I turned into an expansively optimistic and fluent talker. The injections made me forget how weak my body was, and I applied myself energetically to my cartoons. Sometimes I would burst out laughing even while I was drawing.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, PP. 160 – 161.

Over time one shot a day became two, and then three, and then four, and then ten. Yozo had become reliant on the morphine, claiming it was necessary for his work. But these excuses fooled nobody – including Yozo. One day, dejected and disgusted at himself for picking up yet another addiction, he resolved to do a bunch of morphine before throwing himself into a river. Fortunately, Horiki and Flatfish intercepted these plans by throwing Yozo in a car and driving him to a mental hospital.

In his mind, Yozo had finally reached the last social straw. Being forced into a mental hospital, to him, had forever marked him as an outsider – he had completed his slow lifetime detachment from society:

“I had wept at that incredibly beautiful smile Horiki showed me, and forgetting both prudence and resistance, I had got into the car that took me here. And now I had become a madman. Even if released, I would be forever branded on the forehead with the word ‘madman,’ or perhaps, ‘reject.’ Disqualified as a human being. I had now ceased utterly to be a human being.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 167.

Three months after his arrival, Yozo was picked up by Horiki and Flatfish. He was informed of the death of his father who had died a month prior. Following this, Yozo was re-located to a house in the countryside where he was to remain – Flatfish would take care of the expenses and Yozo would be watched over by a sixty-year-old woman. After three years Yozo decided to write out the story I am relating to you now. Here are his parting words:

“Now I have neither happiness nor unhappiness. Everything passes. That is the one thing I have thought resembled a truth in the society of human beings where I have dwelled up to now as in a burning hell. Everything passes. This year I am twenty-seven. My hair has become much greyer. Most people would take me for over forty.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, PP. 169 – 170.

This marks the end of the notebooks. We thus return to the unnamed narrator.

The unnamed narrator describes the scene of how he came to obtain the notebooks and photographs, which were given to him by a woman who worked in a bar that Yozo frequented often. She had been sent them – by who she knew not (likely Yozo himself) – and passed them on to the narrator as she thought the contents of the notebooks would make for a great novel.

“The events described took place years ago, but I felt sure that people today would still be quite interested in them.” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 176.

When talking to the woman they discussed the dark contents inside. The unnamed narrator confessed his desire to place the man in a lunatic asylum (if he had known him personally of course). The woman ends No Longer Human on a strangely optimistic view of our Yozo – but one evidently misread by Yozo’s many masks:

“‘It’s his father’s fault,’ she said unemotionally. ‘The Yozo we knew was so easy-going and amusing, and if only he hadn’t drunk – no, even though he did drink – he was a good boy, an angel.’” – No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, P. 179.

The Life of Osamu Dazai

As I said at the beginning of this video, Dazai’s work often took its inspiration from his life. Because of this, rehashing the man’s life story may seem a little redundant, however, there are a few additional nuances worth bringing up.

Osamu Dazai was born in June 1909 in a small village called Kenagi. His real name is Shuji Tsushima. His parents were extremely wealthy and the family itself was vast in size. Dazai was the sixth child of eleven, and unfortunately, due to his mother’s frequent bouts of ill health and his father’s busy schedule, Dazai was left without parental affection from a young age.

Unsurprisingly, Dazai was a voracious reader in his youth. He was introduced to many classics by a nanny who worked at his mother and father’s house. The nanny taught Dazai to write and became his one and only parental figure. By age sixteen, Dazai knew he wanted to become a writer.

According to a documentary called Begin Japanology: The Life of Osamu Dazai (airing in 2011), Dazai’s foray into the world of hedonism stemmed from the death of his favourite author Ryunosuke Akutagawa who took his own life on the 24th of July 1927 – he was thirty-five years old.

In his teens, Dazai studied Gidayu at a university preparation school in Hirosaki. His life – following the death of Ryunosuke Akutagawa – continued to spiral into drink and drugs, and eventually Dazai began living with a geisha, which resulted in him being shunned from his family.

Around this time Dazai had also began writing for the university newspaper, student magazines, and doing a little poetry on the side.

The first attempt on his own life would be taken at this time as well. At the age of twenty-one, in 1930, Dazai attempted to take his own life by throwing himself into a river. He was with a woman too.

Dazai survived. She did not. Within this same year, Dazai graduated and moved to the Tokyo Imperial University where he studied French Literature. During his time studying, Dazai’s hedonism continued, and not long into his studies, he once again attempted to take his own life in the exact same manner. Once again: he survived, she did not.

Following this second attempt, Dazai returned to the geisha Hatsuyo Oyama. Dazai’s family, unable to deny his internal struggling, offered to support him financially. His family also put a stop to the police investigation surrounding his two attempts. Unfortunately for Dazai, this financial support would soon be cut off following Dazai’s involvement in an underground communist party.

In 1933, Dazai had adopted his penname, and with it, began writing his stories in the Shishōsetsu form, the first example of this appearing in his short story “Resha”. The Shishōsetsu form is often described as the “I-novel” and comprises of a writing style that relies on the lived events of its author. Dazai would become one of the most famous Japanese writers to use this form of storytelling.

Three years following the adoption of his new name and style, Dazai would release his first book The Final Years, a collection of fifteen short stories. The book, whilst not blowing up in popularity, generated enough of a moderate applause to spur Dazai on with his writing.

Buoyed by his little-increased literary reputation, Dazai entered himself into ‘The Akutagawa Prize’, one of – if not the – most prestigious literary awards in Japan. Dazai had entered himself into the competition in 1935 and again in 1936 – the former year was won by Tatsuzo Ishikawa for his novel Sobo, and in the latter year, nobody won. Dazai’s initial entry in 1935 had done better than his last, as he was at least nominated for first place. However, one of the judges did openly critique him for his own attempts on his life.

As seems to be the theme with Dazai, this three-year span of self-literary discovery was not as rosy as one may think. Going back to 1933, Dazai would once again make an attempt on his own life after failing to graduate from Tokyo Imperial University as well as not land a newspaper job upon leaving education. One of the short stories in the aforementioned collection The Final Years was initially the note he left behind before his third attempt. A fourth attempt would come upon discovering that his wife Hatsuyo Oyama had had an affair with one of Dazai’s close friends. Once again, this attempt was unsuccessful.

Fortunately, beginning in 1939 and at the age of thirty, a period of peace finally began in Dazai’s life. He married Michiko Ishihara – a geography teacher – who provided a stable household for Dazai, which allowed him to focus on his craft. Within this timeframe he published Schoolgirl (1939), Run, Melos! (1940), and Return to Tsugaru (1944). In the latter book, Dazai details a three-week return to his childhood home where he reconnects with the nanny who had taught him to write. This book is actually quite optimistic.

The publication of these books would not have been possible were it not for Masuji Ibuse, an established writer who had discovered Dazai when he entered into “The Akutagawa Prize” for the second time in 1936. Through connections gifted to Dazai from Masuji Ibuse, Dazai was able to publish the aforementioned books.

Knowing what we do about the bleak nature of No Longer Human in comparison to a book such as Return to Tsugaru – No Longer Human, keep in mind, would be written and published only four years after – the transition in tone begs the question: what happened?

The defeat to the allies in 1945 brought devastation to the everyday lives of the residents of Japan. The country was shamed, the economy tanked, and people lost most – if not all – of their possessions.

Dazai would be impacted by the aftereffects of war too, to the point where he started drinking again. It was also during this time when Dazai reached peak popularity as a writer. This spike came from the publication of The Setting Sun in 1947. The book was inspired by the experiences of Shizuko Ota whose life had fallen apart after the war. She wrote about her experiences in a diary which helped Dazai in the writing of this novel.

The drinking continued despite Dazai becoming a successful writer, widely regarded all over Japan. He cheated on his wife and had a daughter with the person whom he did the cheating with.

Disgusted by his all-too-familiar spiral into addiction and shame, Dazai abandoned everyone and came upon a beautician by the name of Tomie Yamazaki – the woman Dazai would successfully take his own life with.

In an intense emotional state exacerbated by past failures, post-war Japan, no family, and the vice grip of substance abuse, Dazai had once again resolved to take his own life, and in the same vein as he had done with the short story in The Final Years collection before his third attempt in 1933, Dazai wrote his very last novel.

No Longer Human sold well. Dazai was a literary star, but it didn’t matter to him – nothing mattered to him. Eventually, when the pain exceeded the threshold, on the 13th of June 1948, Dazai left his house, side-by-side with Tomie Yamazaki, and headed for the Tawagama Canal to make his fifth attempt.

Nobody survived.

Dazai’s Attraction With The Youth

When researching the life and work of Osamu Dazai, one of the most frequently brought up facts of the writer was his appeal to young readers.

Dazai’s grave is located at the Zenrinji Temple in Mitaka, Tokyo. A year following the discovery of Dazai’s body (June 19th, 1949 – the same day as Dazai’s birthday) friends and family gathered around Dazai’s grave with intentions of celebrating the author’s life and work. These gatherings were known as The Cherry Blossom anniversary and till this day are still taking place.

The gatherings were spearheaded by a Japanese literary critic known as Katsuichirō Kamei who continued organising these meetings until 1963. A new leadership – the Caretakers Association - took over once he retired.

Despite the new leadership, the organisational aspect of The Cherry Blossom anniversary was unnecessary by the time of Katsuichirō Kamei’s retirement, as by the 1960s Dazai’s popularity had increased in both Japan and western nations.

The man responsible for Dazai’s rise in the latter was Donald Keene who was a key figure in championing and translating classic works of Japanese literature. His translation of No Longer Human was published in 1958.

Thus, even in death, Dazai’s influence continued to grow. As the years have gone on an increasing number of youths have arrived at Dazai’s grave, each year substituting one aging family member and/or close friend for a young fan. In 1992 the Caretakers Association (a band of people close to Dazai who took over from Katsuichirō Kamei) disbanded due to its members simply being too old.

When readers reached Dazai’s grave they all did so with separate intentions. Some went simply to witness the grave, others went to pray and meet likeminded people, and the more devoted Dazai fans arrived with intentions of a conversation with the writer. Nevertheless, no matter the intention of the men and women arriving at Dazai’s grave on June 19th of whatever year they decided to do so, there was always one glaringly obvious consistency among them: they were all young.

The reasonings both for Dazai’s popularity and his demographic are worthy of a deep dive in and of itself, and I will be doing exactly just that in the next section of this video. However, to give an overview of the appeal of Dazai’s work as well as the external factors helping generate a popular readership all over the world, the reasonings behind the rise of Dazai fall mostly to hardship.

Hardship formulates in internal and external ways. In regards to the latter, a professor of modern Japanese literature called Takumi Ishikawa demonstrated in the documentary I mentioned previously how – when calculating the number of students choosing No Longer Human for a book reviewing contest over decades – he noted how Dazai’s novel spiked in popularity in times of economic hardship, those being, the 1990s and late 2000s.

Hardship may also fall to internal factors such as a sense of alienation and loneliness, with Dazai’s work bringing a sense of relation and comfort.

Before I get too carried away, let’s not forget the cultural references to Dazai and his work. One example of this is in the anime Bungo Stray Dogs, a series that features Dazai as a character whose ability is called No Longer Human. We are first introduced to Dazai’s character with his legs pointed out of a river he’s floating down after, you guessed it, an attempt on his own life.

The second notable mention is found in Junji Ito’s adaptation of No Longer Human (published between 2017 – 2018), which – like Dazai’s character in Bungo Stray Dogs – brought even more eyes to Dazai’s novel, particularly those of youth.

On the back of my edition of No Longer Human, the blurb makes the bold claim that No Longer Human is “still one of the ten bestselling books in Japan, […]”, which – at least in my research – I haven’t been able to verify. What I can verify, however, is that No Longer Human is the second bestselling Japanese novel published by “Shinchosha”. Their number one bestselling novel is Kokoro by Natsume Sōseki.

In recent times No Longer Human is still resonating with the youth. In 2023 the book exploded on Tiktok – to the extent that an article was written in The New York Times about it.

No Longer Human had developed a wink-wink-nudge-nudge-if-you-know-you-know type reputation, with Booktok leading the charge on its meme-worthy status. One such video showed a layout of sticky tabs, one colour of which was labelled as “relatable”, the video then cuts to her flicking through the book in slow motion with that colour appearing on almost every page.

Now, I am not going to read too much into a Tiktok trend and a few memes, but it is undeniable that Dazai’s work – and particularly No Longer Human - is resonating with people. Ever since it was published in 1948, generation after generation of young readers have clung to this book life a life raft.

But why? Well, we could consider the typical thoughts and feelings that influence our tastes and preferences when we’re teenagers, such as, angst, insecurity, rebellion, and uncertainty – all feelings that can be found in a Dazai novel. But why is a book – with its bleak depiction of society, total disconnect from human warmth, and general fear of the world itself – consistenly ramping up its sales with every decade that passes by?

General author-book reputation influencing the readership, cultural references, social media: these play a part in the popularity No Longer Human no doubt.

As well, please, for the time being, keep the literary merit of No Longer Human to the side, as when I question the popularity of the novel, I of course understand it is simply a well-written and poetic book.

However, I believe there is a little more to it and it is this additional factor I want to further explore. The clue is in the title, in the content, in the man who put it to paper. It is, of course, a feeling we have all felt and that has been on the rise for the entirety of at least my lifetime:

Loneliness.

Why Are The Youth Resonating?

Perhaps it is just me and my warped algorithm, but am I the only one who every once in a while will find themselves being recommended a video akin to the titles “X years old with no friends”, or “no job, no girlfriend, no future”, or even “X years old, never experienced Y, never had Z”?

I have tried to be as general as possible with these titles so as to not potentially highlight anyone in particular. Nevertheless, the point still stands and I’m sure you all know what I’m talking about or can at least fill in the blanks. Usually these – and I am talking on average – videos will contain a young man sat in his car or bedroom pouring his heart out in a tone of voice that communicates a paralysis of apathy.

The person in question will talk about their lack of human interaction and/or meaning, often jaded by an unfulfilling routine they had sleepwalked into. Guided by a series of pre-determined stages – primary school, secondary school, college, university – the person is suddenly allowed through the backdoor of education and into what he had occasionally been warned about but never prepared for: the real world.

He looks behind him at the stress-free, low expectation, highly social, and free-time-laden world of education and notices the door is closed. Now this person has to adapt to this real world, and in no time, finds himself before a camera with only a series of comments on a screen to talk to. The person confesses his frustration, his disillusion, his deep loneliness. The comment section seems to agree – yet everyone remains apart.

It seems as if the term “loneliness epidemic” is everywhere. In articles, in debates, in videos, in books – it feels as if something which, in theory, should be so easily solved is continually getting worse.

To begin, let’s get a definition of loneliness from the EU Science HUB:

“A negative subjective experience of low quality and/or quantity of one’s social network.” - EU Science HUB

There are two differing types of loneliness: emotional loneliness and social loneliness. The former is a loneliness felt when the relationships in your life do not reach a certain quality; the latter is a loneliness from having no relationships at all.

To feel lonely is to be deprived of something rather inflicted with something. In the same way our stomach pangs when we have gone too long without eating, so too do our minds when we are lacking frequent meaningful connections with others.

Loneliness has become such a notable trend in recent years that many studies and polls have taken place to document its rise. It has been so noticeable that it has altered the way some organisations conduct their studies. Take, for example, the Gallup Global Emotions Report.

Since 2005, the Gallup Global Emotions Report has been publishing yearly updates on the emotional state of the world. The researchers would interview people – whether in person or over facetime – and ask them a series of questions designed to determine their mental state. With the results, the researchers then would be able to identify trends in positive and/or negative experiences, the trends of which, can be presented to those capable of making the decisions necessary to make a difference.

Initially, these researchers would determine the anger, physical pain, stress, worry, and sadness of a pool of interviewees dotted across the globe. However, it was only until 2023 when “loneliness” was added to the list of negative experiences.

In the most recent report, researchers found that over one in five people have reported feeling lonely worldwide. Keep in mind that when these participants are asked these questions, they are asked to recall their emotions from the day prior to the interview. The report showed that whilst reports of loneliness were lower than the other negative experiences – anger, sadness, worry, stress, and physical pain – people who reported feeling lonely often experienced more negative emotions as a result.

With this in mind we must consider term impact of experiencing loneliness. According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NHS (National Health Service), and WHO (World Health Organisation), people who experience long-term loneliness are at risk not only of mental conditions such as depression and anxiety, but also physical conditions like heart disease. Evidently, loneliness deserves the “epidemic” title as it is spreading, attaching itself non-discriminately, and can have dire consequences if not treated. Despite this, loneliness continues to spread around the world.

The most recent Gallup Global Emotions report found that Comoros – a country in East Africa experienced the highest rate of loneliness (reaching 45%) whereas Vietnam experienced the lowest (16%). For context, the United States reached 20%, Australia 18%, the UK 21%, Canada 21%, India 25%, China 23%, and Japan 14%.

The topic of loneliness is one that, like many others, contains subsets and opposing views, all of which, have their place in this sweeping talking point. However, considering the location through which Osamu Dazai and his ever-growing fan base originate, I wanted to elaborate on a form of loneliness that – whilst not being wholly unique to the nation of Japan – was coined in a Japanese phrase by a Japanese psychologist and that has elements of this universal form of loneliness attributable only to Japanese culture. I am speaking of hikikomori.

The term hikikomori will likely sound familiar to anyone with an interest in either the loneliness epidemic or Japanese culture. The full term “shakaieki hikikomori” translates to social withdrawal.

The term and phenomenon was highlighted by Saitō Tamaki who brought attention to this shunned topic in 1998 when he published the book Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End.

When Saitō Tamaki published his book he kickstarted a conversation still taking place now. But what exactly is the definition of hikikomori? Saitō Tamaki gives us this in his book:

“A state that has become a problem by the late twenties, that involves cooping oneself up in one’s own home and not participating in society for six months or longer, but that does not seem to have another psychological problem as its principal source.” – Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End by Tamaki Saitō, P. 24

The last piece of this quote is perhaps the most important part of the term hikikomori. In writing this book, Saitō Tamaki had aimed to directly address the symptom of withdrawal, and in doing so, aim to treat it specifically.

The reasoning for this was because a withdrawn individual’s psychological traits can fall into many things: obsessive thoughts; thoughts of taking one’s own life; abuse; skipping school, etc.

Saitō Tamaki uses the example of someone visiting a doctor with a cold, headache and sore throat. The doctor would not diagnose the patient with a “coughing syndrome” or “headache syndrome” but instead would diagnose the root cause of these symptoms. Social withdrawal needs to be viewed, and thus treated, in the same manner:

“The various symptoms that accompany social withdrawal are sometimes secondary. In other words, first, there is a state of withdrawal from society, and as that state continues, it gives rise to various other symptoms. I believe it is of crucial importance that we think of the hikikomori state as a primary symptom.” – Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End by Tamaki Saitō, P. 26.

Saitō Tamaki gives the example of a patient he had once treated who had fallen into a state of social withdrawal and developed a phobia of himself having body odour. This phobia soon died off but made way for other obsessive compulsions during his state of social withdrawal.

It can also be the case, Saitō Tamaki says, that the act of being in social withdrawal further produces other delusions or obsessive thoughts. In keeping to oneself all day, it would be natural for one to begin to think they could, for example, hear the judgement of others when hearing the voices of their conversing neighbours out the bedroom window. The continual isolation causes one to become suspicious and frightened of people, a feeling enhanced by a lack of interaction with those very people. The withdrawn become withdrawn due often to bad experiences with people, and in not interacting with people, these bad experiences permeate any and every person. A vicious cycle.

Although, speaking of those pesky nosy neighbours bothering our poor hypothetical paranoia-ridden hikikomori with their opinions, let’s be honest, whilst the neighbours in the example may innocently be conversing, we would be lying to ourselves to suggest that a man or woman staying in their room 24/7 for more than six months, never working, never interacting with anyone, and seemingly living in a lazy paradise funded by the ever-flowing cash dispenser of mum and dad, is not being judged for it.

Society naturally looks down on people within the hikikomori state. But, as Saitō Tamaki says, the hikikomori state is nothing to be judgemental of – in fact, it is something to be sympathetic towards. The hikikomori is a continuously fretful individual aware of where he or she is going wrong, but unable to fix it.

“As the symptoms progress and extend over an increasingly long period of time, it simply seems to others that the person is being lazy and acting lethargic, but often, there are deep conflicts and strong, fretful feelings hidden below the surface. As evidence, once can see that the majority of people in withdrawal do not experience boredom, even though they spend their days not doing anything. Their minds appear to be occupied, not giving them the psychological room to feel bored.” – Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End by Tamaki Saitō, P. 23.

The hikikomori mindset is different from what people initially anticipate. Whilst most people chalk up the hikikomori psychology to an outlook similar to someone who is depressed, the reality is quite the opposite. A depressed person, Saitō Tamaki notes, will feel as if all is hopeless, as if there was nothing to live for and that they would be better off dead. The hikikomori, however, whilst flirting with these feelings occasionally, are aware of their potential but are blocked mentally, thus adding to their distress.

This is the unique tragedy of the hikikomori: a clear understanding of where they’re falling short without an understanding of how to break their state of withdrawal. The hikikomori is better to be thought of as a human stuck than voluntarily placed in their room:

“The major difference between their situation and clinical ‘depression’ is that the patient suffering from clinical depression frequently thinks, ‘it’s all too late, there’s no turning back now.’ Many hikikomori patients, however, still are undergoing internal conflict, thinking they would like ‘to do whatever it takes to make a new start,’ and ‘the sooner, the better.’ However, because they do not feel that they have much time or space to carry this out, these thoughts do not transfer into hope, and unfortunately for them, these feelings just transform into irritation and despair.” – Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End by Tamaki Saitō, P. 48.

The personality type prone to fall into a life of withdrawal is naturally introverted, shy, avoidant, and sensitive to shame.

Bad experiences with people and/or the perceived letting down of others can push this personality into the hikikomori lifestyle, as for them it is a defence mechanism which goes too far. A trauma of any type” bullying; heartbreak; abuse; bereavement; failure in a pursuit; any type of intense exterior pressure, etc. All of these events can trigger a state of withdrawal which could take years to come out of says Saitō Tamaki.

My personal favourite aspect of this book is how Saitō Tamaki talks about the trauma people cause as well as our relationship with society. Put simply: people hurt people. We cause each other stress, anger, worry, sadness, and sometimes even physical pain. But we also produce love, kindness, good will, and all that soppy stuff.

Saitō Tamaki speaks on how a hikikomori-like reaction towards bad experiences with people will doing nothing but breed ignorance and prejudice against the human race, If you were to spend five years of school life being bullied, you would naturally develop and associate those bad experiences with humans as a whole. In short you would come to the conclusion: humans suck. However, Saitō Tamaki says, if we choose to reject society and the potential harm it may bring, we also reject the good it can do for us too, and us to it – an even more satisfying feeling.

For a brief period, solitude, and an individualistic attitude (accompanied by some sigma edits) towards life is fine, but to make it the main staple of your social diet is to prepare yourself for a warped delusion regarding the human race. It is only through contact with well-meaning, supportive, and positive people that we can overcome the trauma of life. The hikikomori misses this crucial part of life and find themselves in a never-ending cycle of trauma and loneliness. In the process they fail to mature and thus to grow, allowing for an even deeper state of withdrawal.

“When people ‘mature’, they undergo traumatic experiences, whether or not they like it. But that is not all that happens. It is also important that people who have experienced trauma are provided ample opportunity to recover from trauma. They have the right to be allowed to do so. ‘Traumatic experiences and recovery’ come as a set in the process of maturation. One cannot have maturation without these things. What makes this set of things possible is, of course, contact with others. When one gets hurt, it leaves one with an image of others that is traumatic and frightening; however, when one experiences healing through the support of others, that helps one acquire a more accurate image of others – it teaches that others are not always frightening. In that sense, acquiring immunity to trauma is a process of gaining an appropriate image of others.” – Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End by Tamaki Saitō, P. 97

Something Yozo was never able to do.

Coping With Loneliness Through Art

This “healing through the support of others” is not always an option for people. Therefore, they turn to the artists. Evidently, the hikikomori state is an extreme example of a collective of lonely people in society, however, the intensity of that loneliness is not so different – some just cope in differing ways.

Coping with loneliness through the artistic works of others is a common coping mechanism. Whether it be through film, music, painting, or literature, any medium can provide solace. I would argue, however, that it is only through literature that a true understanding can be felt with another’s mind.

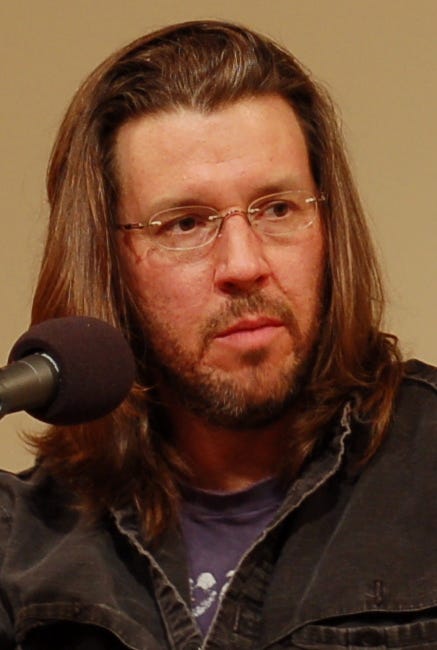

David Foster Wallace often spoke on literature as being a tool against loneliness and best articulated his reasoning in this quote:

“There are a few books I have read that I’ve never been the same after, and I think all good writing somehow addresses the concern of and acts as an anodyne against loneliness. We’re all terribly, terribly lonely. And there’s a way, at least in prose fiction, that can allow you to be intimate with the world and with a mind and with characters that you just can’t be in the real world. I don’t know what you’re thinking. I don’t know that much about you as I don’t know that much about my parents or my lover or my sister, but a piece of fiction that’s really true allows you to be intimate with… I don’t want to say people, but it allows you to be intimate with a world that resembles our own in enough emotional particulars so that the way different things must feel is carried out with us into the real world.” - David Foster Wallace.

I think this is why people (particularly the youth) gravitate towards Dazai’s work, especially No Longer Human.

Going back to the documentary Japanology: The Life of Osamu Dazai, there is a section where they interview Dazai fans outside of his grave and one of them (a young man) says this:

“When I feel sad or lonely I read his stuff, then I feel less alone.”

This sums it up neatly.

I think one of the reasons the youth seem to resonate so much with No Longer Human is due to Dazai’s incorporation of the aforementioned Shishōsetsu form. Also known as the “I novel”, this form of writing gained traction in Japan within the early 20th century and was used by Dazai in many works.

This form – whilst not necessarily having to be – often includes a first-person narrative, as does No Longer Human of course (technically a frame narrative but you get the point). In this form, the personal experience of the author is often relayed and interspliced with confessional thoughts and feelings surrounding the narrative. Within the thoughts are the philosophies and states of mind of our author/narrator.

In utilising this form in No Longer Human, Dazai conveys the alienation of Yozo in an intimate manner. We are told the story itself whilst reading the confessional interior reactions towards that story, Therefore, given the nature of this form, we can see why a youth would feel a kinship with the sweeping generalisations about society, feelings of misunderstanding, and fear of the world, especially if this youth’s angst is enhanced by loneliness.

Where No Longer Human is unique, is in its oftentimes non-emotional manner of relaying Yozo’s inner thoughts. Our Yozo tells us about his clowning – and how he uses it as a mask – in a way that is nakedly honest. He almost has no sympathy for himself or sense of pity.

In writing in the first person, it is easier to identify with the character and slip into seeing yourself in aspects of the narrative. You gain an emotional understanding. It comes back to Wallace’s quote wherein he says that prose fiction allows you to be intimate with a mind in a way you cannot be in the real world. As Dazai relays the life story of Yozo – a life story whose steps such as childhood, school, university, drinking, relationships etc. seem universal – it is no wonder youths find solace in his writing.

Every time I look up a new article or video on No Longer Human, references to this book always – and I mean always - note its relatability, which is a worrying sign given, at least so far, it is the loneliest book I’ve ever read.

The Loneliest Book I’ve Ever Read

No Longer Human has always intrigued me due to its honest portrayal of a man lost.

Dazai transports you to the mind of Yozo, and in doing so, the mind of Dazai – a deeply alienated, flawed, and emotionally lonely individual whose end garnered a reputation incumbent in authors who have tragic ends: the tortured artist trope.

Dazai was a tortured artist no doubt and he made the best of his struggles as he could. He transformed his negatives into the art that today is resonating with a population that could use a little extra reason to stick around, even if the author didn’t feel it was worth doing himself.