Content warning: This post discusses some sensitive content relating to the atrocities that occurred at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

When I told my work colleagues my main inspiration for travelling to Poland was to see Auschwitz, they labelled me a psychopath.

I don’t quite understand why — well, I kind of do, but not really.

I would not suggest visiting Auschwitz to be a courageous act, but I do believe seeing the real thing for yourself puts a lot into perspective and is worth putting yourself through. The weight of the event presses on you in a way that documentaries, books, or figures on death tolls can never do. It’s a show-don’t-tell affair.

And so, when I recount the experience of seeing Auschwitz, I want to note two things: the psychological benefit of witnessing (as best as you can of course) the real deal; and two, Auschwitz itself and the purposes of refining the buildings and what it means to those who were held there.

I hope I can do so as respectfully as possible.

The Arrival at Auschwitz

The day to visit came on Monday, 14th April 2025. I woke up at 5 am in my room in Kraków, drank coffee, showered, read, and left for the Kraków Główny train station at around 6 am.

Auschwitz is located in Oświęcim, a roughly one-hour train ride from Kraków. The town itself is modest and unassuming. Auschwitz is around a twenty-minute-im-going-to-be-late walk from the station, and when you’re there, you could be convinced you weren’t.

If approached from the angle of the train station, Auschwitz appears as unannounced as any city staple deserving a slight acknowledgement. It’s just a “oh wow, there it is” type of feeling - one I did not expect to have. I had wrongly assumed my introduction to the place would mirror the photos seen online: the long train track stretching under the arch of an elongated entrance building (as seen in the photo above). Already, my ignorance was becoming apparent.

Instead of my preconceived ideas of the place, the front entrance was nothing more than a flat concrete wall outside a bus shelter with a rectangular hole through which two L-shaped lines of people were protruding: one for those who already have tickets (those on the left), one for those who don’t (the right). I was in the former.

The privilege of thinking ahead granted me direct access to the front doors, through security, and into the main lobby (I guess you could call it that), where you wait for your tour guide. The main lobby is reminiscent of a multi-storey car park with a reception in the centre. The floor, ceiling, beams, and receptionists’ desk all sport varying colours of grey, and the sound of differing languages reverberates from the walls endlessly.

The only relief of colour is in the (roughly) forty-inch TV hanging above the seating area displaying the names of many tours of the day, along with the preferred language it will be conducted in. There are school trips, random men/women on their own (like me), nuclear families, partners, and groups of friends: all of them supposed psychopaths in the eyes of my work colleagues.

I realised I had made my first mistake when I noticed the stickers. Tour guide expectants had all been easily distinguishable via the genius move of a sticker announcing their preferred dialect for their tour. Mine, as a typical one-dimensional UK resident, was going to be, no, had to be in English. I went to the reception and got a sticker. I have since lost this sticker.

Admittedly, I was curious about Auschwitz for more than just the incidents occurring within the concentration camp itself. I am not a seasoned traveller; however, I have been to my fair share of monuments/museums/historical sites. Some include Napoleon’s Tomb, the Lochnagar Crater, and Rosenborg Castle. All sites differ from your typical museum in that you are visiting the real deal. You get to stand where many before you have stood and attempt to imagine what it would’ve been like to be a contemporary. However, where Auschwitz differed was in its etiquette and reputation.

Etiquette

Auschwitz is a different type of historical site. It was a concentration camp designed to kill Jews, the disabled, homosexuals, gypsies, prisoners of war, political enemies etc., in as efficient a way as possible. The camp saw 1.1 million men, women, and children killed. I will get into the details of this later, but for now, just know (although I am sure you all do) that Auschwitz demands an etiquette unlike many historical sites on your average holiday.

Throughout the years, articles and videos had popped up in my feed displaying the disrespectful nature of visitors at the site. These accounts of disrespectful visitors would range from kissing in certain blocks that display the leftover possessions of those killed in the camp, or taking smiling selfies outside the entrance, or stealing parts of the site itself, or in some cases throwing up Nazi salutes for a joke. Since Auschwitz was converted into a historical site, it has been subjected to the public’s ever-present spectrum of stupidity.

On the Auschwitz website, the rules ask that you dress appropriately (suits and ties not needed, just don’t dress in a way that suggests you’re doing anything fun afterwards. I.e., tank top and/or shorts, t-shirts with funny graphics, sandals and socks, to name a few), take photos in areas where you are permitted to, and generally “observe the appropriate solemnity and respect.”

Photos cannot be taken in blocks four and eleven, nor can any photos be taken with flash, and lastly, photos must “not violate the good name of the Victims of Auschwitz.”

In short: the rules demand common sense.

Fortunately, when I was there, everybody, besides one person who whipped out their phone in block four (to her benefit of the doubt, she may have just misheard as she immediately put her camera away when asked to), was acting as you should do: respectfully.

Beginning of the Tour

My tour congregated at exactly 9 am. We were led into the basement, given headsets, and introduced to our tour guide. This guy was brilliant. He was a Polish man of – if I had to guess – around 40 years of age who stood at 6 feet 1, sporting a black cap, black T-shirt, black buttoned shirt, blue jeans, and green shoes.

Throughout the tour, our guide retained what, in retrospect, was the appropriate tone and delivery. He managed to combine a respectful yet disgusted demeanour. He never said “um” or “ah”, or for one second looked bored reciting what I presume he has nearly word-for-word been reciting since 2007 (I asked him when he did his first tour). Thanks to the headsets they gave us to hear him properly, his voice was a strong companion to the horrors of both the main camp of Auschwitz and Birkenau (two distinct camps I will explain later).

The tour begins on the route to the main camp. Before reaching the entrance (the entrance that displays the words “Arbeit Macht Frei” meaning “work sets you free”), we stop by a long wooden building and are instructed to go inside, where we will watch a three-to-four-minute film detailing a brief history of the camp and what to expect.

In short, this video is designed to set the tone. Before now, our group had been hanging around, conversing, checking out the bookshop, and drinking coffee. We needed to emotionally acclimate.

The video immediately introduces you to images displaying deceased victims and presenting the scale of the slaughter. To my surprise, there is no mention of how to behave (there shouldn’t have to be, but you know what some people are like) with regards to the above-mentioned rules. We left the movie room and headed for the entrance.

The main camp of Auschwitz was formerly a military base the Nazi’s occupied in 1940. After its occupation, the name was changed, and Polish prisoners of war were kept in the barracks. It is important to note this distinction.

For the first year of Auschwitz, it was mostly Polish prisoners of war. When comparing the design of the buildings from Auschwitz’s main camp to Birkenau (the latter being an area of Auschwitz more commonly shown in the media), the quality and size are noticeably different. The main camp consists of sturdier structures and is more condensed, whereas Birkenau stretches over a vast plain of greenery, the constructions of which are mostly shack-like.

Almost immediately, you are filed into blocks where you are shown SS Officers’ offices, photographs of the victims who perished (these photographs contained the date of arrival and date of death; It was rare to see these dates last more than three months), canisters of Zikylon B (one canister could kill one-to-two thousand people and the Nazi’s had literal tons of the stuff), 3-D printed (I assume?) models displaying areas of the camp, and small closet-like rooms where people were locked inside to die of starvation, among much more. As you ascend and descend the blocks, you can’t help but notice the erosion of the steps.

Our tour guide noted how, despite the main camp still being a place of much suffering, this area of Auschwitz was considered the “nicer” part due to the prisoners being given access to basic facilities such as washrooms and toilets.

Being shown the rooms in which people had died, along with photographs of rows of victims (with context added by our guide, of course), did not help hit home the gravity of Auschwitz so much as did block four and eleven. As previously mentioned, these two blocks are the only two areas in Auschwitz where you are asked not to take photographs. The reason is due to the contents inside.

Inside these blocks were the leftover belongings and parts of the victims. By parts, I mean their hair. In one room, a glass container around half the size of your average UK train carriage was full to the ceiling with hair. This hair was shaved off the dead victims and sold to companies who used it for mattresses and pillows.

Maximilian Kolbe

Between blocks, our tour guide would gather us around to provide more context. His information mostly consisted of anecdotes ranging from humanity at its worst to humanity at its best.

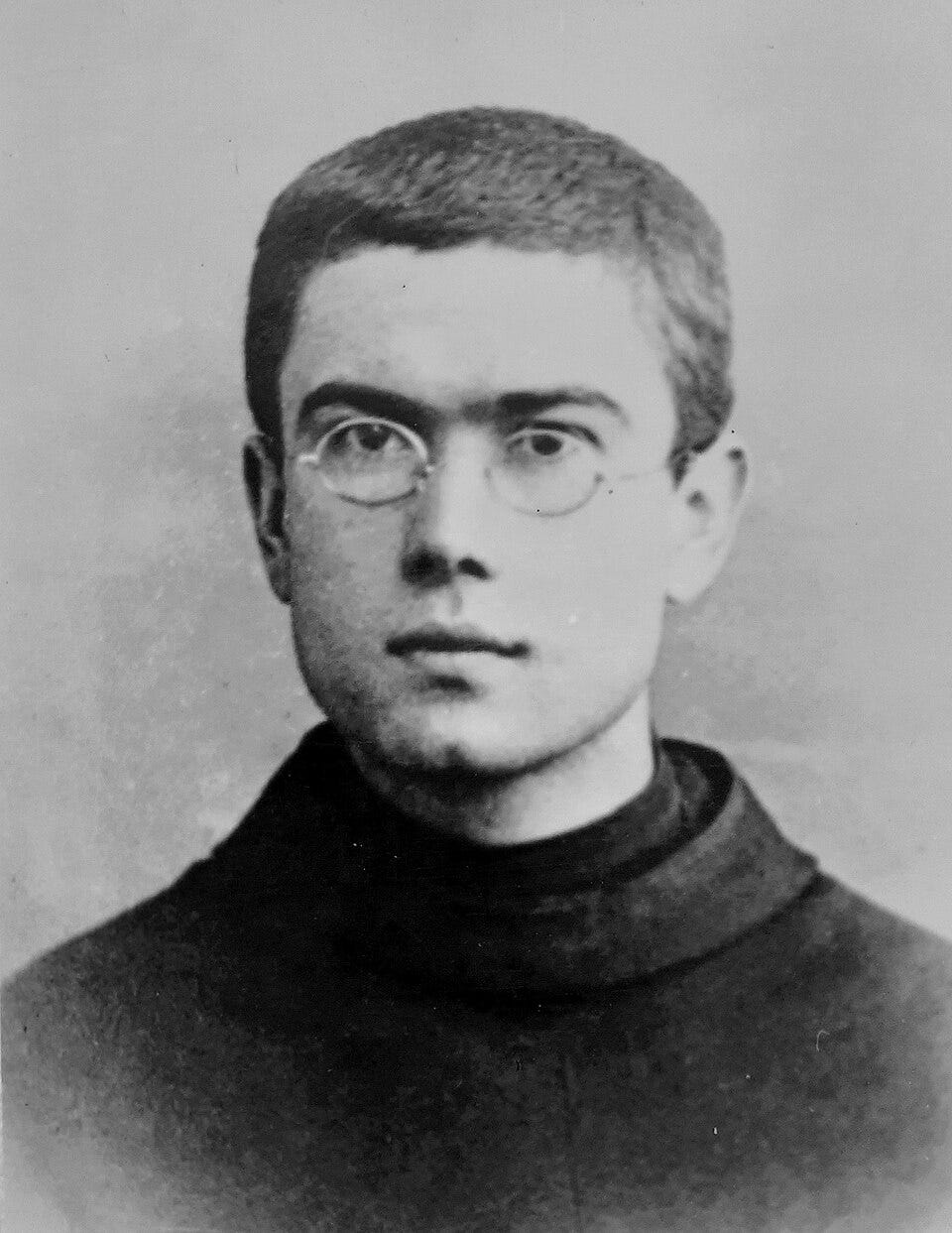

Regarding the latter, our guide told us of a priest named Maximilian Kolbe who volunteered to take the place of a fellow prisoner who was condemned to death. The block Kolbe and this man were from was being punished due to someone from their block escaping. This was a routine punishment used to prevent future escapees.

SS Officers were picking out ten people to be starved to death. The last man to be picked was a Polish sergeant named Franciszek Gajowniczek. Stood next to him was Maximilian Kolbe, who volunteered to take his place. Kolbe – along with nine others – was stuck in a cell and left to die. A week later, the officers opened his cell to find him still alive. Needing space for another set of condemned men, the officers took Kolbe to the “hospital” to be executed via lethal injection to the heart. Franciszek Gajowniczek survived Auschwitz and died in March 1995 at the age of 93.

Survival in Auschwitz

You may be wondering how Franciszek Gajowniczek managed to survive four years in Auschwitz. Our guide explained how survival in Auschwitz was partly due to smarts but mostly down to luck. Survival in Auschwitz relied heavily on the type of work you were made to do. The first priority is to find shelter. Many of the jobs required of the prisoners was manual/labour-intensive, and thus, consisted of long hours (10 – 12 hours a day) in the Polish cold in thin clothing. Add on top of this the fact that all men (roughly) consumed 1500 calories a day, and you can see how the wrong combination of these two elements could result in death.

Often, the people who survived Auschwitz were male, young (early 20s), multi-lingual, and worked in the kitchen. Males were useful to the Nazis simply because they could be used for intense physical work. However, if a prisoner became too exhausted to keep up with the pace of the others, they would be killed. Thus, being young increased your level of survival due solely to being able to cope with the demands of the officers. Being able to speak German helped out prisoners too, as they were able to humanise themselves with the officers and ask for more favourable conditions. By “favourable conditions”, I mean being able to ask to work in the kitchen (surprisingly, sometimes simply asking just worked). The kitchen, for one, sheltered you from the cold, and two, the kitchen granted you easy access to additional rations. However, if any of the prisoners were caught smuggling food or taking more than their fair share, they would be punished severely, and most often, sent to die.

End of the First Half of the Tour

We ended the first half of our tour in front of where Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss was hanged in April 1947.

Höss was an SS Officer in command of Auschwitz from its inception to 1943. He was responsible for the many deaths of its inhabitants, and he lived in a house within the camp itself. His wife and children lived in this house too (his wife famously wrote in her diary that their new home was a “paradise” despite being within earshot of the extermination of the Auschwitz prisoners).

After Germany lost the war, Höss went into hiding but was eventually found and soon sentenced to death. He was hanged outside of the house he had lived in, and just outside the camp’s gas chamber. A film called The Zone of Interest was released in 2023 and details Höss’ life at the camp itself. I haven’t seen it myself, but apparently it is worth a watch if any of this intrigues you.

After learning of Höss’ story and looking at where he was hanged, we walk inside the gas chamber and are shown where the pellets of Zyklon B were inserted.

Throughout the tour, you cannot help but try to imagine what it was like to be a prisoner. This, of course, is impossible to do (especially seeing as our visit coincided with a sunny spring day in April); however, physically entering the gas chamber gives you the closest to an understanding as you can get.

Our guide explains how sometimes these chambers were so cramped that the dead would still be standing once the door was opened. I looked at the walls for any evidence of scratch marks, but couldn’t see any noticeable ones. Mostly, those led into these chambers were none the wiser and were only made known of their fate as it was happening. Thus, to try and understand is to try and adopt the ignorance of those crammed inside, which is impossible to do. Not one person could for a second view this place other than for what we know it was, no matter how hard they attempt to do so.

The first half of the tour ended there. We were guided back towards the main lobby and asked to meet outside the bus shelter at 11:10 am. The bus would take us on a five-minute ride to Birkenau, where the majority of the killing (as well as the majority of our understanding of Auschwitz) took place. I took the allotted time to make some notes.

Dark Tourism and Morality

I think now would be a good time to reflect on the moral questions we must ask ourselves when visiting historical sites whose history itself is based on human suffering.

Auschwitz is one of the popular examples of what some people have referred to as a location rife for “dark tourism”, which, in essence, is the seeking out of places wherein tragedy has occurred.

Some other locations include Chernobyl, the 9/11 memorial site, Robben Island, and the Choeung Ek Killing Fields, to name but a few. Essentially, anywhere suffering has taken place and been preserved for tourists to see for themselves.

I struggled with the moral implications of my intrigue in Auschwitz. As explained at the beginning of this article, when I told people my intentions of travelling to Poland, they labelled me a “psychopath”. Now, whilst this labelling is in jest and partly influenced by my (according to my colleagues) personality (again: according to my colleagues. I actually happen to think I’m alright [“something a psychopath would say!” they would probably reply]), the fact everyone unanimously took to questioning the reasoning behind my intrigue in a location where men, women, and children were tortured, gassed, starved, worked to death, and burnt, is completely fair, and in all honesty, I couldn’t answer the question satisfactorily even to myself. In essence, intrigue was my guiding principle in this decision, and whether that alone was morally wrong was not entirely clear to me.

Dark tourism was coined by a professor of tourism at Glasgow Caledonian University in Scotland, called Prof. J. John Lennon. According to Lennon, when speaking to The Washington Post in 2019, dark tourism is not a new phenomenon.

Lennon relates our fascination with darkness to that of the general public, who would gather to witness public hangings in 16th-century London, or to evidence suggesting people were watching the Battle of Waterloo play out from far-off carriages in 1814. In essence, humans are naturally intrigued by suffering and tragedy. The individual reasons for that intrigue, however, are worth interrogating.

By interrogating, I of course mean exploring the “why” behind people’s intrigue in human suffering.

Take, for example, the gore videos that used to circulate on websites like LiveLeak.com or the subreddit r/watchpeopledie. For those lucky enough not to know (but unlucky enough not to be able to figure it out), these two examples (the former being a website, the latter a forum) would consist of videos of real people dying in multiple ways. The type of person dying would range from a random man/woman to a highly influential political leader, and the type of death could be a complete accident (a car crash) to intentional (assassination).

The same type of intrigue in suffering is seducing people to watch these videos, but in my opinion, the “why” is shallower. As opposed to physically visiting a historical site - an area which contains additional information, opportunity for donation, tour guides, and a sense of reality to the suffering itself – the people watching these types of videos (I have been one of these people in the past) are scratching an itch. It’s the equivalent of watching porn and getting laid: overexposure to the former can be psychologically damaging, and in turn, warp the reality of the latter to the detriment of both you and others. Thus, the “why” is pure entertainment and nothing more. You’re not attempting to understand or learn anything, but instead trying to gratify a need to know. It is that distinction between understanding and knowing that morally justifies the intrigue.

When considering my own “why” for visiting Auschwitz I do believe it was eventually answered, however, my “why” was not apparent to me upon initially booking the tour. But for now, let’s get back to the tour itself and we can pick this back up later.

Birkenau

The second half of the tour takes place at Birkenau. It is here where I began taking some photographs, which I will post further down below. Before now and throughout the remaining tour, our guide stressed the fact that a majority of prisoners never saw the main camp of Auschwitz. Birkenau was where the trains full of prisoners would arrive. The prisoners would be hauled off and separated into two lines: one was for men, the other for women and children. 80% of the people arriving at Birkenau were immediately sent to a chamber and killed.

It is worth mentioning too, that the prisoners were not aware of what was going to happen. From testimonies of those who had survived Auschwitz, they said most people were under the impression they were, at worst, at a work camp. There are multiple reasons for this: the gas chambers were hidden, the prisoners were often exhausted upon arrival, they were also allowed to bring their belongings, and any prisoners expressing concern/asking too many questions were dragged from the crowd of arrivals and executed to prevent the majority from becoming unruly.

Birkenau was an ever-expanding death camp. Even in the days when the war seemed all but lost, the SS Officers managing Birkenau did not stop with their killing. Instead, they escalated the process.

When you step out on the site, it consists mostly of torn-down buildings stretching ahead as far as you can see. According to our guide, a third of the camp was deconstructed upon the liberation of the prisoners in January 1945. However, thankfully, the Russian army had sought to retain what buildings the fleeing Nazis could not destroy. The last of the Nazi’s stopped performing their duties a week prior to this liberation.

Our guide walks us up to where men, women, and children were subjected to the selection process. Online, you can see photographs of these processes taking place and see frame-by-frame as a collection of prisoners (all not fit to work according to that day’s selection officer) are lured towards the gas chambers. A poignant way to put everything into perspective was conveyed at the beginning of the tour: most prisoners spent less time at the camp than we will on our tour.

Isolated amongst the greenery is one carriage. Our guide walks us up to the carriage’s entrance and explains how these were what the prisoners would be sardined into. Some journeys lasted from Greece, and sometimes upon arrival, Nazi officers would open up the carriage doors to find people either dead or near death. Knowing a near-death prisoner was of no use to them, they would immediately send them to the chamber.

We continue walking up the train line towards a large stone pavement embedded in the mud. Our guide pivots whilst pointing out all the former locations of the chambers, which had been destroyed when news of the Russian army’s arrival had reached the officers. We scan the ruins and approach one of the few preserved rooms where the prisoners were kept. We circle the perimeter, and our guide, lit only by the entrance opening, tells us of the need to preserve the site.

The “Why”

The purpose of allowing an area like Auschwitz to be open to the public is to keep alive the memories of those who died and survived the concentration camp.

Our guide estimated there were a few hundred people left alive who were in Auschwitz before its liberation, and soon, the only relic remaining of that time would be what we were seeing right then and now.

Auschwitz is evidence. Just remember, the Nazi’s wanted to cover up everything that occurred there, and between 1940 – 1945, they were able to (as best they could) keep everything under wraps. The place was a well-oiled and efficient death camp that continued running up until a week before it was liberated. It was always expanding and getting increasingly better at extermination.

In the wake of the fleeing Nazis there were many buildings brought down, papers and belongings burnt, and even prisoners moved further West. Fortunately, there was simply too much to cover up and not enough time, and thanks to some clever soldiers arriving at Auschwitz 80 years ago, the site was prevented from being torn down purely for one reason: evidence.

The tour ended there.

Our guide (whose name I do not know) thanked us all for our contributions, and he received a round of applause. On the walk back towards the bus that was to take us to the main camp, where I would split for the train station, I wondered why he did what he did.

Did he know anyone personally impacted? Was it simply just a job? (I doubt it), Or was he just a history buff? From small snippets of conversation, all I could tell was that he had been doing this trail since 2007. Despite this, he never seemed jaded or desensitised. As he relayed much of the information I have done above, he did so in measured disgust – that is the only way I can describe it.

Would you label him a psychopath? I don’t think so. I believe there is merit to this “dark tourism” thing (I don’t like that name, but for consistency's sake, I’ll use it).

As mentioned previously, when you’re at Auschwitz, you cannot help but try to imagine what it was like. Evidently, this is not possible. However, going to an area like Auschwitz and seeing the real thing hits home the gravity of depravity a lot harder than mere facts and figures. There is a bigger purpose to seeing areas where tragedy has taken place.

And to do so doesn’t make you a psychopath.